In our previous post, we looked at the effects that the reopening of state economies across the United States has had on consumer spending. We found a significant effect of reopening, especially regarding spending in restaurants and bars as well as in the healthcare sector. In this companion post, we focus specifically on small businesses, using two different sources of high-frequency data, and we employ a methodology similar to that of our previous post to study the effects of reopening on small business activity along various dimensions. Our results indicate that, much like for consumer spending, reopenings had positive and significant effects in the short term on small business revenues, the number of active merchants, and the number of employees working in small businesses. It is important to stress that we are not expressing any views in this post on the normative question of whether, when, or how states should loosen or tighten restrictions aimed at controlling the COVID-19 pandemic.

As in the previous post, we rely on variation in the reopenings across states and time to distinguish the effects of reopening from other possible confounding factors. Different states reopened on different dates starting in April, and this variation allows us to compare, at a given point in time, states that had already reopened with states that had not yet reopened. Further, by looking at the trends of the variables of interest in the period immediately before reopening and checking that there are no differences in trends prior to reopening, we are confident that any differences in activity post-reopening are indeed capturing the causal effect of reopening.

Measuring Small Business Activity Using High-Frequency Data

We use two sources of high-frequency data on small business activity. The first, Womply, is a software-as-a-service provider focused on customer relationship management. It collects settled credit card transaction data for businesses processing payments with one of Womply’s processing partners. Womply serves more than 450,000 small businesses all over the United States, with good coverage across a broad range of industries. We use Womply data to look at total small business revenues as well as the number of merchants conducting business.

The second source of data, Homebase, provides a software interface for scheduling employee hours and for general payroll purposes. It is used by more than 100,000 businesses and their hourly employees. About 90 percent of Homebase clients have fewer than 100 employees, and in fact most coverage is among very small firms and establishments. Most of the Homebase coverage is concentrated in the leisure and hospitality and retail trade sectors. We use Homebase data to look at the number of employees working at small businesses.

For all variables studied here, we take U.S. states as the geographic unit of analysis; we compute each value as a weekly average and then rescale it by its average January level. As in our previous post, we combine the state-week level data with information on each state’s reopening from the New York Times database. To isolate the causal effect of reopening on small business outcomes, we follow the same event-study methodology as in the previous post (see here for more details.) It is important to note that we are considering short-term effects (up to eleven weeks after reopening) and our analysis cannot speak to longer-term effects. Further, in all the charts shown below, the confidence bands of our point estimates become large with the passage of time, and we cannot reject the eventual unwinding of the estimated effects to zero—which could also indicate convergence of all states after they have reopened.

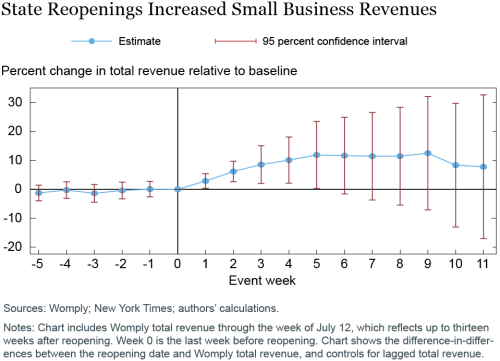

The chart below shows a significant positive effect of reopening on small business total revenues from Womply. The blue dots present our point estimates for the change in total revenues relative to the baseline in each week before and after reopening, while the red lines indicate 95 percent confidence intervals. The point estimates suggest that reopening increased small business revenues by more than 10 percent by week five following reopening. Intuitively, this coefficient represents the difference in revenues between states that reopened five weeks before and states that had not yet reopened at that point. After week five, the increase in revenues seems to plateau. The absence of statistically significant and economically important differences between states that had reopened and states that had not in the weeks before week zero gives us confidence that the study is uncovering a causal relationship.

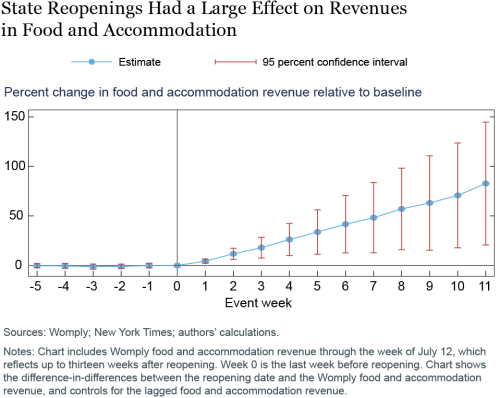

As we did with consumer spending, we observe some interesting heterogeneity across industries. The chart below examines the effect of reopening on small business revenues in the food and accommodation sector. The effect is statistically significant for all weeks after reopening and is economically large, with the point estimates indicating that revenues grew by more than 50 percent by week eight. Reopening also had a positive effect on revenues in the healthcare sector and a negative effect on grocery revenues (neither shown here). These patterns are qualitatively consistent with those observed in consumer spending in our earlier post.

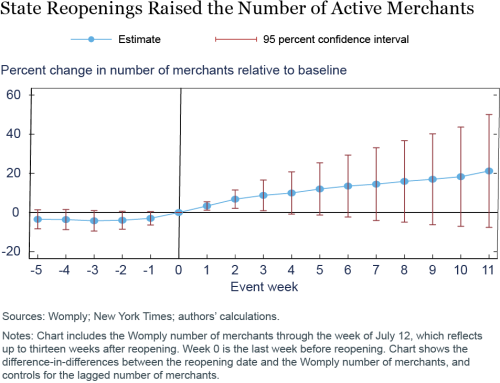

The next chart looks at the number of merchants conducting business, another series available from Womply. Here we see a positive effect of reopening on the number of active merchants, which is statistically significant in the first three weeks after reopening. The point estimates grow from about 10 percent in week four to about 20 percent by week ten, although the confidence bands become quite large in later weeks. This measure does not plateau further out after reopening, as was the case for total revenues.

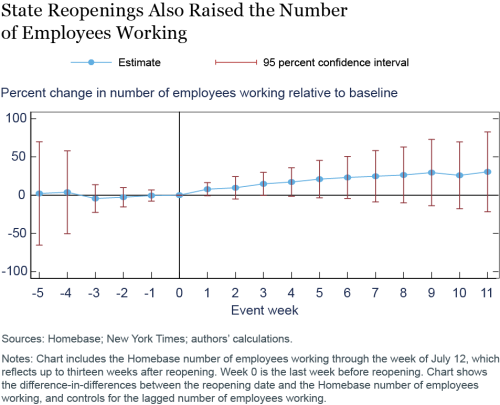

Finally, the last chart uses Homebase data to examine the effect of reopening on employment at small businesses. Here, too, we find a positive effect of reopening on the number of employees working. The effects are marginally statistically significant for the first and third weeks after reopening, but otherwise not statistically different from zero at the 95 percent confidence level. The magnitude of the effects varies from about a 15 percent increase in week three to a more than 25 percent increase by week ten—a relatively large effect, although one needs to keep in mind that since the units of analysis are small businesses, the aggregate effect in terms of additional employment will be modest. In this analysis, as in the previous chart, we again do not see any significant differences in pre-reopening trends, adding confidence to a causal interpretation of our results.

In sum, our analysis suggests a positive effect of reopenings on small business outcomes, similar to what we found for consumer spending in our previous post—although it is important to bear in mind that we focus here on short-term effects. In July, the resurgence of the pandemic in many states forced some to pause their reopenings and others to tighten restrictions again. In addition, the positive effects of reopening may be dampened as consumers and businesses become more cautious and adopt more stringent social distancing in response to the rising number of COVID-19 cases in their localities. Our results are consistent with the presence of significant economic benefits to reopening, which may be tempered by the resurgence of the pandemic.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sebastian Heise is an economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Sebastian Heise is an economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is an economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Davide Melcangi is an economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

Related reading on Liberty Street Economics:

Did State Reopenings Increase Consumer Spending? (September 18)

How to cite this post:

Rajashri Chakrabarti, Sebastian Heise, Davide Melcangi, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Giorgio Topa, “How Did State Reopenings Affect Small Businesses?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 21, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/09/how-did-state-reopenings-affect-small-businesses.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics