ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — A Supreme Court of Canada decision regarding a judge’s error in the jury selection process for the trial of two men charged with terrorism offences will be closely watched in this province, given the reasons for a recent mistrial in RNC Const. Doug Snelgrove’s sexual assault case.

The country’s top court ruled Wednesday that an Ontario judge’s mistake in the jury selection process for the trial of two men convicted of terrorism offences did not affect their rights and doesn’t warrant a new trial. The court has yet to release details of its reasons for the decision.

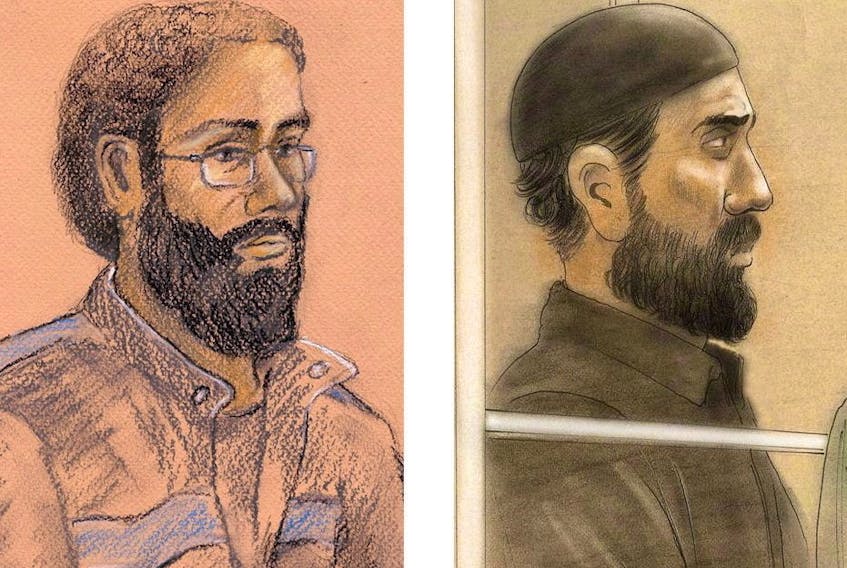

Raed Jaser and Chiheb Esseghaier were convicted in 2015 of terrorism charges related to a plot to derail a VIA Rail train travelling between Toronto and New York. The two men appealed their convictions, arguing their jury had been improperly constituted due to an error by the trial judge.

The jury selection process for Jaser and Esseghaier had proceeded by way of challenge for cause, a practice that sees potential jurors questioned by lawyers in an effort to determine their ability to be impartial.

The process is often used in high-profile cases that have seen significant media coverage and attention before going to trial. It was used most recently in this province last month in the trial of Snelgrove, 43, who is charged with sexually assaulting a woman while he was on duty in St. John’s in 2014.

Once two jurors are selected, they become ”triers,” having a say in whether or not others are accepted as part of the jury before Crown and defence lawyers make the final call. Each selected juror replaces one of the two triers.

Jaser had requested that other prospective jury members be excluded from the room while the process was happening, but the trial judge ruled he had no discretion to exclude the prospective jurors due to an amendment to the law. At the time, the law around jury selection was in flux and there was debate over whether the discretion to grant a request like Jaser’s existed; the Ontario Court of Appeal decided last August the judge had erred and granted Jaser and Esseghaier a new trial.

The Crown appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which heard the case Wednesday and denied the men a new trial, saying the original judge’s error had caused no harm when it came to their rights to a fair process.

That was the same argument prosecutor Lloyd Strickland made at Snelgrove’s trial last month when the judge mistakenly dismissed two extra jurors before sequestering the rest to begin their deliberations.

Justice Garrett Handrigan had opted to keep 14 jurors in the jury box throughout the trial, then dismissed two just before deliberations began, by telling jurors No. 13 and 14 they could leave. The usual procedure is to dismiss alternate jurors this way before a trial begins. If a judge decides to keep more than 12 jurors in the box to hear the evidence, they are usually considered additional jury members, not alternates, and jurors are dismissed by a random draw of numbers.

Handrigan realized his mistake an hour later, and asked Strickland and defence lawyers Randy Piercey and Jon Noonan for their submissions on how to proceed. Strickland argued the error had no effect on the jury’s impartiality at that point, and submitted deliberations should continue; Piercey and Noonan argued their client’s rights had been breached and a mistrial was the only option. In their submissions, the defence lawyers quoted a decision from the Ontario Court of Appeal issued four months earlier in which a trial judge who had made the same mistake — dismissing an additional juror without a random draw — and it was ruled a fatal mistake.

“The purpose of (the law regarding a random draw) is to ensure that the trial judge discharges additional jurors impartially. The random dismissal procedure helps prevent a trial judge from ‘hand-picking’ the final composition of the jury based on their observations,” that decision read, the judges noting there had been no suggestion the Ontario judge had been biased.

Neither is there that suggestion of Handrigan, who acknowledged his mistake was not recoverable and declared a mistrial.

“Essentially you are not a properly constituted jury,” he told the jurors. “I’ve considered possible remedies and I don’t find one that’s suitable in the circumstances at this time. In the circumstances, I don’t think I could possibly undo any damage that might have been done to ensure that you are properly constituted to come to a verdict.”

Snelgrove is set to go to trial again in March 2021. It will be his third time being tried on the charge, having been acquitted in 2017 before the Crown appealed and a new trial was ordered. It will also be the third time the complainant will be called to testify before a jury.

Women’s rights advocates have staged demonstrations since the mistrial was declared and are calling for judicial reform and training for justice system participants related to sexual assault cases, saying the process is undermining complainants' faith in the system, further traumatizing them and intimidating them about reporting sexual violence.

“I understand that the argument for the mistrial was that by having those two jurors not dismissed randomly, and the randomization of jurors is an integral part of a jury trial, it somehow compromised the jury. It didn’t,” advocate Heather Elliott told The Telegram at Snelgrove’s arraignment last Monday. “The average person who sits on the jury isn’t going to be aware of the rules and isn’t going to say, ‘Hey, how come those two were (dismissed)?’ It didn’t compromise the jury, it compromised the attorneys’ opinion of the jury, which is a whole other thing.”

Neither Strickland nor Noonan were available for comment Thursday.