Featured Resources

Fiscal Brief

April 2021

Changing Neighborhoods:

The Status of New York City’s Capital

Investments in Rezoned Communities

PDF version available here.

Summary

Since 2014, the de Blasio Administration has succeeded in winning approval for the rezoning of six neighborhoods as part of its Housing New York plan. To help assuage community concerns about the rezoning of neighborhoods from East New York in Brooklyn to Bay Street in Staten Island, and to recognize the infrastructure needs created by an increase in residents and workers, the Mayor agreed to numerous local projects as part of the rezoning initiatives. These projects range from new schools and parks to roadway improvements.

IBO has looked at the funding status for the 87 capital projects agreed to as part the six rezoning initiatives approved to date. Among our findings:

The Covid-related fiscal turbulence experienced by the city over the past year cast some doubt over the availability of funding for many planned capital projects, including those that are part of the neighborhood rezonings. With the recent influx of federal aid, the outlook for funding many of these projects, at least in the near-term, has improved.

Introduction

In May 2014, Mayor de Blasio released the Housing New York (HNY) plan, with the initial goal of building or preserving 250,000 affordable units for extremely low- to middle-income New Yorkers. That goal has since increased to 300,000 affordable units over a 12-year period. Central to the implementation of the HNY plan was the idea of Mandatory Inclusionary Housing coupled with the large-scale rezonings of neighborhoods. Passed into law in 2016, Mandatory Inclusionary Housing requires developers in areas rezoned to increase residential density to reserve a share of apartments in their projects as permanently affordable housing, with the share depending upon the affordability level. Tied to the passage of Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, the HNY plan called for the rezoning of city neighborhoods to drive the production of new market rate and affordable housing.

The HNY plan also underscored the city’s recognition of the need to make substantial investments in the infrastructure of communities undergoing rezoning changes in order to absorb the anticipated influx of new residents and workers while also bringing benefits to long-term residents. The lion’s share of this infrastructure funding is in the capital budgets of city agencies. To supplement this agency funding, the de Blasio Administration also created a $1 billion Neighborhood Development Fund (NDF). This special fund includes $329 million earmarked for citywide water and sewer infrastructure investments through the Department of Environmental Protection and $703 million in dedicated infrastructure funding specifically for neighborhood rezonings. This neighborhood-specific portion of the NDF is managed entirely by the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC), a nominally private, not-for-profit entity that is controlled by the Mayor.1

In this study, the Independent Budget Office uses data from rezoning agreements and capital budget documents to determine what infrastructure measures—projects promised at the time neighborhood rezonings passed—have been funded in the budget. Specifically, IBO reports on the status of New York City’s efforts to invest in the infrastructure of the six communities that the city has rezoned under the HNY plan: East New York (Brooklyn), Downtown Far Rockaway (Queens), East Harlem (Manhattan), the Jerome Avenue Corridor (Bronx), Inwood (Manhattan), and Bay Street (Staten Island).

In analyzing these neighborhood-scale rezonings, IBO compared data from rezoning agreements, capital funding from city agencies, and the $703 million in NDF funds to distinguish between capital initiatives that currently have funding in the budget and those that do not. Our analysis includes an examination of capital initiatives by spending category, the date when these projects were initiated, and the underlying source of the capital funding.

Background

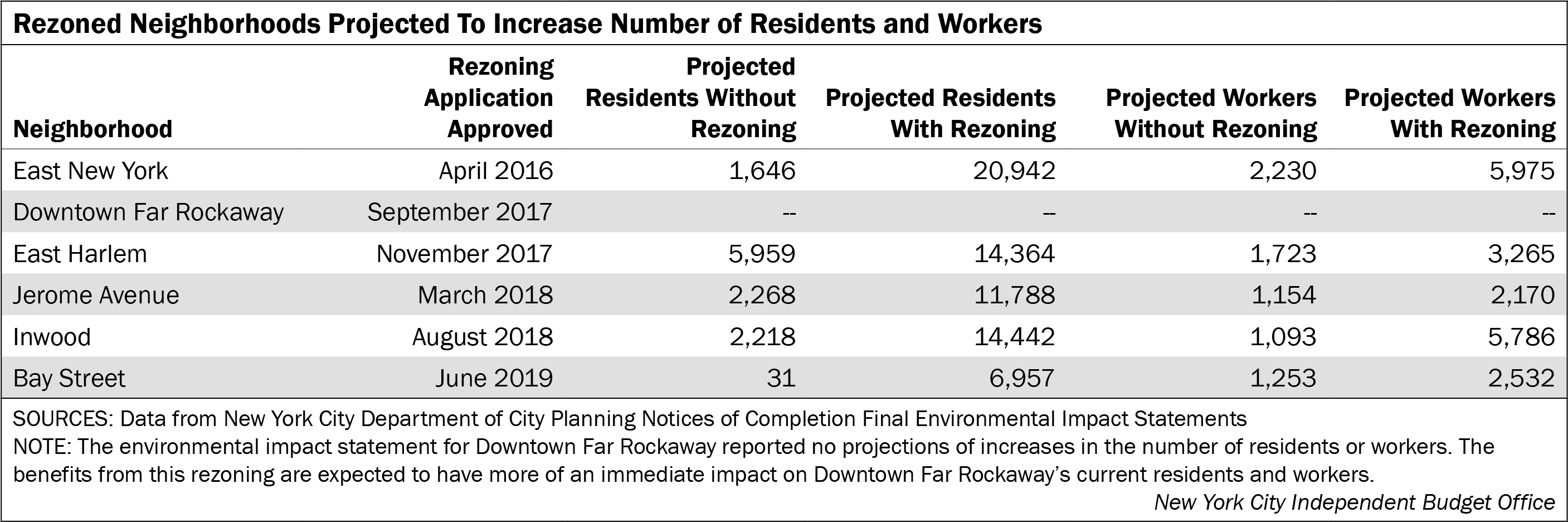

At the nexus of the HNY policy to rezone neighborhoods and the promises of capital investment stands a city planning process to assess the needs of the communities affected by rezoning. From a demographic standpoint, community needs are driven by anticipated changes in the number of area residents, workers, and local businesses expected from the rezoning. According to the city’s environmental impact statements, which are part of the review process leading up to a rezoning approval, East New York was projected to add the most residents (+19,300) and the Inwood rezoning was expected to bring about the largest increase of workers (+4,700).

Ultimately, figures like these point to anticipated increases in residential and economic activity, which would also necessitate more schools and open spaces, improved roadways, and other investments in brick and mortar infrastructure that will enable neighborhoods to absorb the increase in density while maintaining or raising the quality of neighborhood amenities for both current and future area residents.

Before the approval of a neighborhood rezoning by the City Council, neighborhoods slated for rezoning underwent a process of community input, in which the city engaged area residents, businesses, advocates, and policymakers to identify infrastructure needs and concerns of the community. The rezoning plan then cycles through the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process, leading up to a final vote by the City Council to approve or reject the plan. Although the community review process is time intensive and involves many public reports and meetings, the process has been criticized repeatedly for moving forward while ignoring the concerns of local residents, particularly those from marginalized communities.

In order to address concerns of local residents and businesses in neighborhoods facing rezonings, the city negotiated Points of Agreement for each of the six approved neighborhood-scale rezonings, which are published through the office of the Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development. Examples of capital investments specified in the Points of Agreement documents include the development of a new waterfront park, construction of a new 800-seat school, and improvements to roads with bike lanes and added protections for pedestrians. In addition to capital projects, Points of Agreement can also include agreements on expense budget funding for services such as workforce development training and anti-harassment legal services for area tenants. To increase transparency around this process, following the approval of the East New York rezoning in April 2016, the City Council passed Local Law 175. This law requires the city to make public a list of all community benefits negotiated and recorded in the Points of Agreement for each neighborhood rezoning. The Mayor’s Office of Operations publishes this list, the NYC Rezoning Commitments Tracker, online. At present, the tracker has logged over 300 community benefits.

Despite the Points of Agreement specifying promised capital improvements, the city’s extensive land review process, and the enhanced transparency afforded to the public through Local Law 175, misgivings about the touted benefits of neighborhood-wide rezoning persist. Following approval by the City Council, opponents of the Inwood plan filed suit and the New York State Supreme Court annulled the Inwood rezoning in December 2019, siding with the claim of neighborhood advocates that the city did not sufficiently take into account the needs of the community, specifically when it came to the potential displacement of existing residents.2 The city filed an appeal soon afterward, and the Appellate Division ruled in late July 2020 to reinstate the Inwood rezoning.3 Despite the lawsuit, the capital projects created in connection with Inwood’s rezoning plan continued even as the city’s appeal worked its way through the legal system. With the advent of the coronavirus pandemic in New York City, however, future neighborhood rezonings such as Gowanus in Brooklyn have been delayed. While the state Supreme Court has just allowed the Gowanus plan to begin the formal review process, with about eight months remaining in the de Blasio Administration’s term, time is running out to complete other rezonings before a new Mayor is sworn in. Nevertheless, the city’s promise to fund capital improvements in six neighborhoods as approved by City Council continues to move forward.

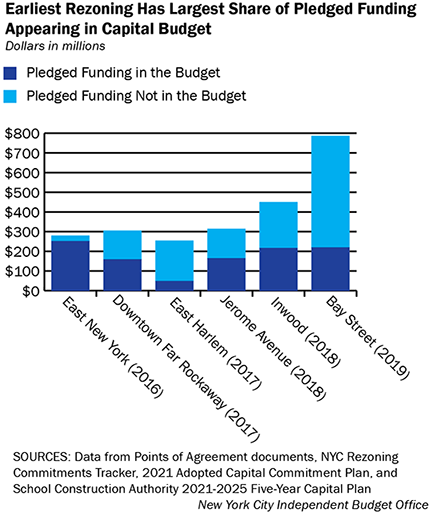

Capital Funding Pledged by the City

In our review of the Points of Agreement for the approved rezonings of East New York, Downtown Far Rockaway, East Harlem, Jerome Avenue, Inwood, and Bay Street, IBO found that the city pledged to spend a total of $2.35 billion to fund 87 capital initiatives. Bay Street and Inwood, the two most recent rezonings, have the largest amounts pledged at $782 million and $449 million, respectively. The pledged amounts for the other four rezonings range from $252 million (East Harlem) to $311 million (Jerome Avenue).

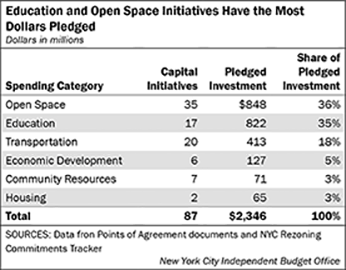

To examine the various types of capital initiatives among the 87 identified in the Points of Agreement, IBO looked at projects in terms of the six distinct categories of spending described in the NYC Rezoning Commitments Tracker: education; open space, which encompasses parks, playgrounds, and waterfronts; transportation, including streets and related substructures; economic development; community resources such as community centers and libraries; and affordable housing. These categories cover capital funding for the creation of new structures as well as enhancements or improvements to existing community infrastructure.

In terms of pledges by spending category, open space initiatives and education have the most dollars pledged ($848 million and $822 million, respectively), followed by transportation ($413 million). Economic development, community resources, and housing initiatives comprise the smallest share of overall pledged funding, totaling $263 million.

Pledge Amounts Appearing in the Capital Plan

Based on the $2.35 billion in capital pledges detailed in the Points of Agreement documents, IBO identified the projects and funding that actually appear in the city’s 2021 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan, published by the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget in November 2020. We also used the 2021-2025 Five-Year Capital Plan from the New York City School Construction Authority as a supplement to identify funding for education-related initiatives.

IBO’s examination of the city’s capital commitment plan (also referred to as the capital budget) identified 18 capital initiatives where city funding exceeds the amounts pledged in the Points of Agreement for those specific projects. These overages range from $200,000 to $17 million per rezoned community. This extra funding, totaling $37 million, increases the overall funding pledged by the city to enhance the infrastructure of the six rezoned communities to nearly $2.4 billion. Our analysis going forward is based on this revised total pledge amount.

Fully Funded Versus Partially Funded Initiatives in the Capital Budget. IBO found that nearly half of the capital dollars pledged by the city in the Points of Agreement for the six rezonings appear in the city’s current capital budget to fund specific rezoning-related projects. This funding totals $1.05 billion and is earmarked to fund 69 capital initiatives across six neighborhood-scale rezonings. There is also around $370 million of rezoning-dedicated NDF funding not yet allocated to specific projects. These remaining NDF funds, held by EDC, can be drawn down in future budgets to fund rezoning projects that are currently not funded or only partially funded.

Twenty-four capital initiatives, totaling $365 million, have the full amount pledged by the city in the capital plan. Examples of fully funded initiatives range from $412,000 to resurface portions of Fulton Street and Ridgewood Avenue to approximately $100 million for the creation of a 1,000-seat school, both projects in East New York. The remaining 45 capital initiatives, which together total $689 million, have partial funding in the capital plan.

The number of projects fully funded in the Adopted 2021 Capital Commitment Plan declined from the number in the 2020 adopted plan as the forecasts of growing budget shortfalls brought on by the pandemic, as well as the pause in nonessential construction for part of the year resulted in changes in many areas of the city’s capital budget. The city’s financial outlook has brightened since last June, with stronger-than-expected tax revenues and direct federal stimulus funds. As a result, more shifts in the city’s capital budget are likely leading to further changes to plans for individual rezoning projects.

When viewing the budgeted pledges across rezonings, it is not surprising that the share of pledges without funding in the capital plan is larger for more recently approved rezonings. Notably, the amount of budgeted pledges for Bay Street’s capital initiatives exceeds the other rezonings, although as a share of total pledged funding, Bay Street is only one-third funded. This is due to the fact that the city has pledged roughly $785 million to enhance the infrastructure of this community, compared with roughly $320 million on average for the other neighborhood-scale rezonings. East New York has the highest share of funded pledges in the capital plan (at 90 percent), not surprising given that it was the first neighborhood to rezone under the HNY policy. As time goes on, the expectation is that the funding gap for the other rezonings will shrink as the city continues to satisfy its pledges to these communities.

Some Capital Initiatives Counted Towards Fulfilling Pledges Predate the Rezonings

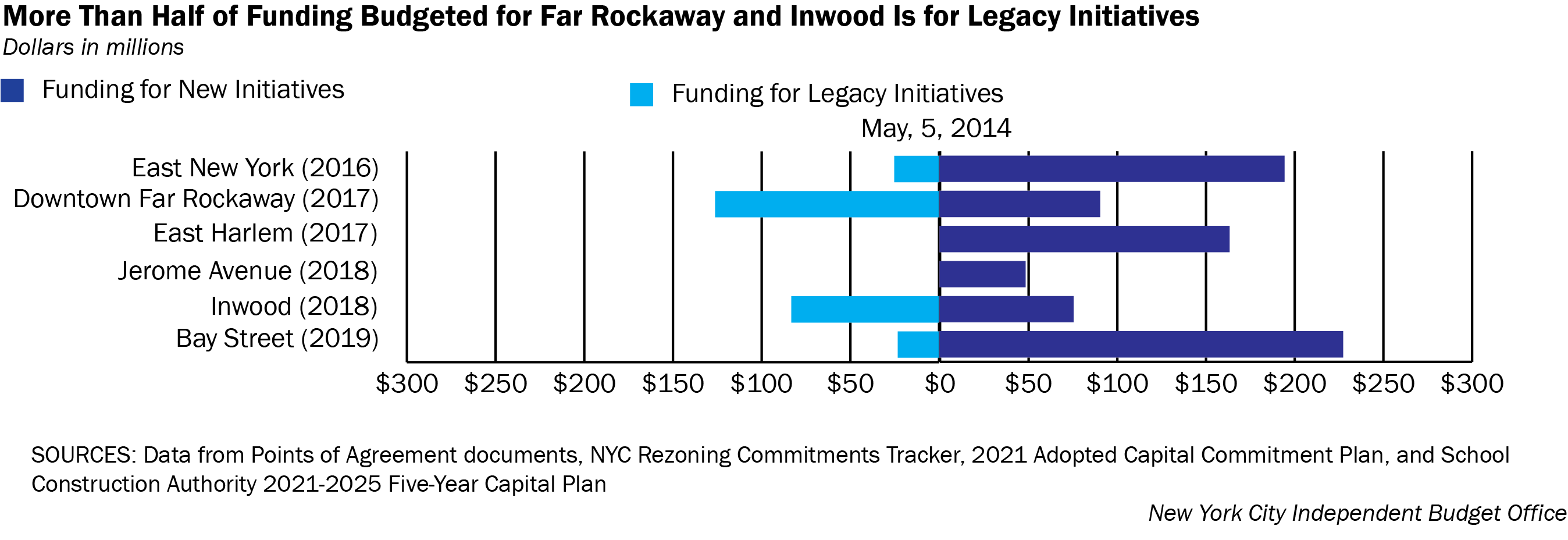

Looking across the $1.05 billion in pledged funding presently in the capital plan for the six neighborhood-scale rezonings, IBO next examined how closely these capital dollars reflect the planning process that culminated with the City Council’s approval of the six rezoning plans. In doing so, we relied on the date the overall HNY plan was first unveiled by the Mayor in order to distinguish capital initiatives that were formulated as part of the rezoning process from capital initiatives that predate the Housing New York policy.

In comparing the capital initiatives listed in the Points of Agreement documents with the initiatives funded in the capital budget, IBO found that some initiatives existed before the HNY plan was announced. Extreme cases include the rehabilitation of the Broadway Bridge in Inwood, a project whose origins date back to 1999, and upgrades to sewer infrastructure at targeted locations in East New York, dating back to 2008.

While the de Blasio Administrtion implicitly acknowledges these older initiatives by specifying the amount of “new city funds” in each of the Points of Agreement documents, these letters do not indicate the point in time that the city used to delineate new from older funding. IBO used the date the HNY plan was released, May 5, 2014, to distinguish the newer capital initiatives that were formulated during the planning process for each neighborhood-scale rezoning from those legacy initiatives whose origins predate the HNY policy. We believe this approach allows IBO to credit some projects that may have been in the works before the area was officially rezoned as new, while flagging others that were conceived well before the rezoning plan was announced as a mayoral priority. This is generally consistent with the city’s own estimates of “new city funds.” Based on the May 2014 cutoff date, IBO found a total of $797 million in new funding in the budget for 59 new initiatives and $256 million in the budget for 11 legacy initiatives.

East Harlem and Jerome Avenue, each have no legacy initiatives. With only a sliver of East New York’s budgeted pledges going to fund three legacy initiatives, the lion’s share of its capital funds are new as well. On the other hand, at 58 percent, Inwood has the largest share of funding for legacy initiatives. This is followed by Downtown Far Rockaway and Bay Street, whose legacy initiatives account for 53 percent and 24 percent of the funding in the capital plan, respectively.

It is important to note that the decisions to include legacy initiatives in the Points of Agreement documents for the East New York, Downtown Far Rockaway, Inwood, and Bay Street rezonings were just as strategic as those that created newer capital initiatives in all six rezonings, in that existing and new neighborhood priorities are weighed and balanced. The Points of Agreement negotiations and the ULURP process for each rezoning effectively placed these legacy projects, which were not specifically tied to the expected rezoning population growth, on equal footing with the newer projects. As the legal proceedings around the Inwood rezoning demonstrate, the actual needs of a community facing rezoning will invariably be a source of ongoing—and often impassioned—debate, no matter the age of its infrastructure projects.

Source of Funding in the Capital Plan

IBO traced the source of the $1.05 billion in pledge amounts presently in the capital plan, breaking the funding down into dollars coming from city agencies’ capital budgets and the funding coming from the NDF. IBO’s analysis of the sources of capital funding of the 69 capital initiatives with $1.05 billion budgeted in the capital plan found that 68 percent of capital dollars were sourced from city agencies with 32 percent sourced from the $703 million NDF.

The larger funding share, totaling $717 million for 45 capital initiatives, flows directly from the individual capital budgets of nine city agencies: Administration for Children’s Services; and the Departments of Citywide and Administrative Services, Design and Construction, Education, Health and Mental Hygiene, Housing Preservation and Development, Parks and Recreation, Transportation; and the New York Police Department. EDC serves as the “managing agency” for six of these initiatives, with its own capital budget—entirely separate from the $703-million NDF it also manages—funding 14 percent ($97 million) of the total agency-sourced dollars in the capital plan.

In contrast, $337 million in capital funding flows directly from the NDF towards 29 capital initiatives. Three initiatives—creating publicly owned sites in East New York for job creation uses, development of the Harlem River Greenway Link, and development of new parks along the Inwood Greenway (including construction of the Sherman Creek Malecón and the restoration of the North Cove)—have funding managed by EDC ($68 million). The remaining $269 million in NDF allocated funding is distributed by EDC for other city agencies to manage.

EDC’s management of capital dollars allocated from city agencies and its direct management of the entire NDF indicates the extent to which the city is using this public benefit corporation to carry out the pledged infrastructure improvements versus traditional city agencies.

East Harlem and Jerome Avenue have the largest shares of capital dollars sourced from the NDF, at 49 percent ($23 million) and 39 percent ($63 million), respectively. The NDF also accounts for nearly a third of the capital dollars budgeted for East New York, Inwood, and Bay Street. In contrast, Downtown Far Rockaway ($34 million) has very little of its capital funding sourced from the NDF, at 22 percent.

IBO also observed a marked contrast in the distribution of agency versus NDF funding across spending categories. The NDF makes up more than half of the capital dollars budgeted for open space initiatives ($259 million), while community resource, economic development, and transportation initiatives have far less than half of their budgeted funding coming from the NDF. Education initiatives ($301 million) receive no NDF funding.

In terms of projects, five capital initiatives, totaling $158 million, account for nearly half of all budgeted NDF capital dollars: reconstruction of the Cromwell Recreation Center at the Lyons Pool Site in Bay Street; the Inwood Greenway improvements; renovation and expansion of Grant Avenue Park in Jerome Avenue; renovation of Callahan-Kelly Playground in East New York; and development of the Harlem River Greenway Link.

Committed Versus Planned Capital Funding

IBO next considered the distribution of this funding over time. In IBO’s evaluation of the 69 capital initiatives with $1.05 billion budgeted in the capital plan, we distinguished funding the city is contractually obligated to spend in past or current years from the funding that the city expects to contract out in future years. For the purpose of this discussion, capital commitments budgeted for the six neighborhood-scale rezonings occurred from 2016 through 2021, while planned amounts for future commitments are assessed from 2021 onward.

Planned amounts can be increased, decreased, or pushed forward into later years if necessary, making them much less set in stone. In contrast, committed amounts are as good as money the city has already spent, as it is infrastructure funding that is tied to specific work orders under contract. IBO found that nearly half ($486 million) of funds in the capital plan were committed from 2016 through 2021, while over half ($568 million) of the funds are planned as future spending from 2021 through 2026.

Committed Funding. So far, the city has committed $486 million from 2016 through the first part of 2021 to fund various capital initiatives in the six neighborhood-scale rezonings, with more than half used for education initiatives.

Four education projects alone account for $219 million of the already-committed funding: $104 million for the construction of a new public school located at 3269 Atlantic Avenue in East New York; $56 million for the development of pre-K and 3K facilities in Bay Street; $32 million for the construction of an annex at P.S. 33 in Jerome Avenue; and $27 million for the construction of a new public school located on Targee Street in Bay Street.

Open space initiatives to develop parks, playgrounds, and waterfront infrastructure are included in all six rezoned communities. Over half ($54 million) of these open space commitments were spent in Inwood and Bay Street, at $28 million and $26 million, respectively. Notable among these open space initiatives: $23 million for enhancements to Highbridge Park in Inwood and $16 million for the phase II and III development of the Stapleton waterfront in Bay Street.

The remaining 28 percent of the committed funding presently in the capital plan is comprised of community resources, transportation, and economic development initiatives, totaling $137 million. Over half of the dollars committed for community resource initiatives ($22 million) went towards the replacement of a library in Downtown Far Rockaway. Over two-thirds of the dollars committed for transportation initiatives ($61 million) was for East New York—the majority of which ($47 million) went towards pedestrian safety and water and sewer improvements along Atlantic Avenue. Lastly, the entirety of the $3.5 million committed for economic development initiatives went towards establishing publicly owned sites in East New York for job creation uses.

Planned Funding. In addition to these commitments, the city’s capital budget includes $568 million in planned funding, which is money the city expects to commit from the latter part of 2021 through 2026 to fund various capital initiatives in the six neighborhood-scale rezonings. This funding is subject to change, along with the timelines of the various initiatives expected to receive these planned capital dollars.

The largest share of this planned funding is for open space initiatives at $276 million, followed by transportation initiatives at $174 million. Notable among the planned amounts for open space initiatives is further work on the Inwood Greenway, and construction at the Lyons Pool site and Grant Avenue Park. The largest planned amounts for transportation include $63 million to rehabilitate the Broadway Bridge in Inwood (in addition to the $2.5 million already committed), $24 million to improve priority intersections along 10th Avenue in Inwood, and $18 million for safety improvements from Richmond Terrace to Swan Street in Bay Street.

Only one education initiative is among the planned projects: $48 million to build a new elementary school at 2355 Morris Avenue in Jerome Avenue (in addition to the $758,000 already committed). Implementation of the plan to redevelop the business district in Downtown Far Rockaway ($42 million) accounts for 94 percent of the amounts planned for economic development initiatives.

Pledge Amounts Not Yet Appearing in the Capital Plan

With nearly $2.4 billion pledged by the city, but only $1.05 billion in the capital plan, this means that over a half of the promised funding (56 percent) is not yet in the budget. This $1.3 billion in outstanding pledge amounts is comprised of the $938 million required to fully fund 45 capital initiatives that presently have partial funding in the capital plan, and $392 million for 18 initiatives that have no funding in the capital plan.

Partially Funded Initiatives. Bay Street, Jerome Avenue, and Downtown Far Rockaway comprise 76 percent ($713 million) of the pledged amounts required to satisfy 45 initiatives that already have partial funding in the capital plan. When broken out by spending category, over 80 percent of the pledge amounts required to satisfy these 45 initiatives relate to education and open space initiatives. Outstanding funding for partially funded capital initiatives include: $223 million to complete the construction of a new public school located on Targee Street in the Bay Street; $32 million to complete the construction of an annex at P.S. 33 in Jerome Avenue; $82 million to complete the expansion of the Harlem River Greenway Link to connect 125th and 132nd Streets; $73 million to complete the Tompkinsville Esplanade in Bay Street; and $51 million to complete the renovation of Bayswater Park in Bay Street.

Unfunded Initiatives. Bay Street and Inwood—two of the most recent rezonings—along with East Harlem—have 73 percent ($285 million) of the pledge amounts for 18 initiatives that presently have no funding in the capital plan. When broken out by spending category, education and housing initiatives comprise 71 percent ($183 million) of the initiatives with no funding in the budget.

The largest of these unfunded initiatives include: $78 million to build a new elementary school at 155 Tompkins Avenue in Bay Street and $29 million to install air conditioners in all East Harlem schools; $88 million to repair waterfront infrastructure along the Harlem River (from south of Dyckman Street to West 155th Street) and $45 million to build new infrastructure along the Stapleton waterfront in Bay Street; a combined $65 million to invest in public housing improvements in East Harlem and in Bay Street; $25 million for renovations of La Marqueta in East Harlem; and $15 million to create a new cultural and research center to celebrate the immigrant experience in Inwood.

It is important to note that with this funding not presently in the budget, the initiatives they will fund amount to promises that the city has yet to fulfill. If these promises are not funded before the end of the Mayor de Blasio’s term, rezoned neighborhoods would look to future mayoral administrations and City Councils to continue the neighborhood investments.

The Outlook for Capital Investment for Future Neighborhood-Scale Rezonings

From its release in May 2014, the Housing New York plan set an ambitious goal of rezoning more than a dozen neighborhoods, coupled with the city investing in the infrastructure of those communities. This study has addressed the status of the city’s pledged capital investments towards the six neighborhood-scale rezonings that have made it through the approval process to date. With Mayor de Blasio’s tenure set to end in December 2021, consideration of the future of the HNY goals in general and the rezoning efforts in particular have begun.

Such considerations include the feasibility of funding capital investments in additional neighborhood rezonings, which, if approved, would increase the city’s current pledge of nearly $2.4 billion to fund infrastructure improvements in affected communities. Currently, about a third of all rezoning project funding in the 2021 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan draws from the NDF, with the other two-thirds of funding stemming from city agencies’ capital budgets. With only about $370 million remaining in the NDF for future commitments, it is unclear how far this dedicated infrastructure fund will stretch, especially if the current or future administrations pursue the rezoning/inclusionary housing strategy in additional neighborhoods.

The past year has also seen volatility in the capital commitments for rezoned infrastructure projects. Similar fluctuations have occurred in other capital priorities such as the Housing New York affordable housing plan. The recently announced influx of federal stimulus money to the city’s coffers may mean that the city is willing to take on more debt service or use some of the funds for pay-as-you go capital. In either instance this would increase the funding for pledged rezoning projects.

Recent court decisions blocking and subsequently reinstating the Inwood rezoning demonstrate the challenges that lie ahead for any future rezoning plan. The multilayered land use review process, including Points of Agreement negotiations and Local Law 175, are intended to help ensure that community needs are heard—a goal some residents and businesses in these neighborhoods contend is not met. Even before the pandemic, local support for the proposed rezonings of Bushwick (Brooklyn) and Southern Boulevard (the Bronx) had eroded in the wake of the short-lived reversal of the Inwood rezoning. Rezoning of Gowanus, in Brooklyn, and the SoHo-NoHo neighborhoods, in Manhattan, were in the works when the pandemic shutdown the city; efforts to re-start those initiatives have reignited debates over the city’s rezoning goals and community-review process.

While it is possible that ultimately only six neighborhoods will be rezoned under the de Blasio Administration, these changes have brought substantial ramifications for the future of these neighborhoods, including at least some of the promised infrastructure improvements. It remains to be seen how large an impact neighborhood-scale rezonings will have on the Mayor’s housing plan or whether the next administration will make good on completing the current Mayor’s pledges to invest in the infrastructure of these communities.

Report prepared by Conrad Pattillo

PDF version available here.

Endnotes

1The Economic Development Corporation is overseen by a 27-member board. The Mayor directly appoints 7 members (including the chairperson). An additional 10 members are appointed by the chairperson from a list put forward by the Mayor. The remaining 10 board members are nominated by the Borough Presidents and City Council Speaker and appointed by the Mayor.

2Northern Manhattan is Not For Sale, et al v. City of New York, https://iapps.courts.state.ny.us/fbem/DocumentDisplayServlet?documentId=ohnOnriTnXSFDkH80Bx1KQ==&system=prod (accessed 02/25/2021)

3Following the Appellate Division’s decision to reinstate the Inwood rezoning, Northern Manhattan is Not For Sale filed a motion for leave of appeal, a request for New York State’s highest court to review the Appellate Division’s decision. In November 2020, the New York Court of Appeals declined to hear the case, and the appellate court ruling stands.

PDF version available here.