Known as the “Lady with the Lamp,” Florence Nightingale provided care and comfort for British soldiers during the Crimean War. She helped revolutionize medicine with her no-nonsense approach to hygiene, sanitation and patient care and turned nursing into a valued profession.

Nightingale rebelled against her privileged background

The daughter of a wealthy landowner father and a mother descended from generations of merchants, Nightingale was born in Italy in 1820 while her parents were on an extended vacation. A smart but retiring girl, she shied away from her mother’s zeal for social status, including the expectation that Nightingale would marry a suitable man and settle down to raise a family.

She was well educated in the classics and showed an interest and aptitude in caring for the sick living near her family’s estate in Derbyshire. She was deeply spiritual and would later write about the “divine calling” from God that she experienced as a teen which inspired her decision to pursue nursing. Her parents were horrified — at the time, nursing was considered a profession for the lowest of classes and for many patients, admittance to crowded, dirty hospitals often meant death. But after refusing the marriage proposal of a suitor because she clamored for a more fulfilling life, her parents finally relented. She traveled to Germany and later France to study, picking up many of the organizational and nursing skills she would later champion.

The Crimean War was the beginning of her hygiene movement

After briefly serving as superintendent of London’s Institution for Sick Gentlewomen in Distressed Circumstances, Nightingale found herself called into action following the outbreak of war in 1853 between Russia and the allied forces of Britain, France and the Ottoman Empire.

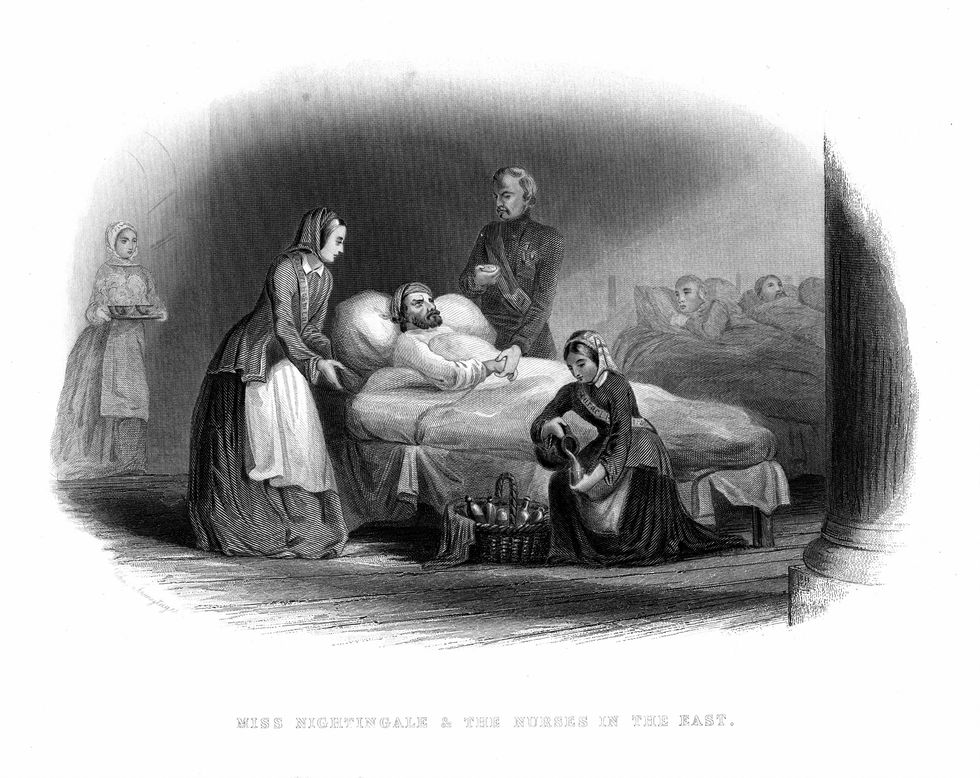

In 1854, news reports began carrying alarming headlines of the dangerous, deplorable conditions in British hospitals outside of Istanbul (then Constantinople). Nightingale swung into action, and by October, she and nearly 40 of her trained nurses were on their way to the front. They were shocked by what they found — severe overcrowding, poor food supplies, shoddy management and filthy quarters that were a breeding ground of infectious diseases like cholera, typhoid, typhus and dysentery, leading Nightingale to dub it the “Kingdom of Hell.” Male British officials initially refused to allow the women to work in the hospital, only relenting when a new wave of battle casualties flooded the ward.

Nightingale and her nurses went to work, scrubbing every inch of the facilities, insisting on regular bathing of patients and frequently changed, fresh linens from a newly established laundry. She solicited donations from Britain to purchase desperately needed bandages and soap and served specialized meals out of a new commissary. She railed against the poor ventilation and sewage system, insisting on bringing as much fresh air to the facility as possible, a decision that would influence the building of future hospitals around the world.

Within six months of her implemented changes, the hospital’s mortality rate had dropped precipitously from its previous high of 40 percent. Nightingale also introduced new approaches to the emotional and psychological side of patient care, with her nurses helping soldiers write letters home and Nightingale herself walking the ward at night with a lantern to check on her charges.

The nurse used statistics to prove that her theories worked

Upon her return from the Crimean War, Nightingale quickly put her fame to use. At the behest of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, she wrote an extensive study, using her records to highlight the deadly toll of poor hygiene and sanitary conditions in British Army hospitals and military camps, leading to a massive reorganization of the British War Office.

One of the first to adopt what is now known as the “pie chart,” Nightingale also developed “Coxcombs,” or “rose” charts, which she used to assess mortality rates from the Crimean War, using applied statistics to differentiate from deaths caused by disease versus those due to battle. Nightingale estimated that 10 times as many British soldiers died from disease than combat during the war.

As British control of the Indian subcontinent expanded, she was pressed into duty again, developing a series of surveys sent to military installations and hospitals, which led to medical and scientific improvements for both soldiers and civilians across India. She would even consult with doctors and medical professionals in the United States, using her data and studies to advise on sanitary conditions in field hospitals during the American Civil War. Her achievements led to her selection as the first woman admitted to the Royal Statistical Society.

Nightingale revolutionized the nursing profession

Using donations and a sizable gift from the British government for her service in Crimea, Nightingale established the Nightingale Training School for Nurses, based at London’s St. Thomas’ Hospital, in 1860, followed two years later by a school for midwives. Women flocked to the schools, as previous notions of nursing as a lowly occupation faded away. Every nurse received one year of training and coursework followed by a two-year stint in hospital wards, after which many of them brought her gospel of cleanliness and care to medical facilities around the world.

Despite increasing ill health from diseases she had contracted during the war, which left her bedridden, Nightingale wrote extensively. Two of her works, Notes on Hospitals and Notes on Nursing: What it Is and What it is Not, laid out her theories for future generations of health care professionals and remain in print to this day. They include practical advice on key topics, including the need for fresh air and ventilation, dietary rules, how to compassionately (but honestly) care for the desperately ill and, of course, good sanitation and hygiene, including the dictum: "Every nurse ought to be careful to wash her hands very frequently during the day. If her face too, so much the better."

She was a pioneer in the field of public health

Nightingale’s accomplishments soon expanded past the confines of hospitals, turning her attention to Britain’s teeming, overcrowded slums and filthy workhouses, which saw the sick poor, including children, the mentally ill and those with incurable illnesses housed together. She worked with social reformers and urban planners on pioneering studies that shed light on the crushing medical, emotional and financial burdens of Britain’s poor.

She advised philanthropist William Rathbone on the development of a new “district nursing” plans, which saw skilled, trained nurses sent out to minister to the public in both hospitals and private homes, first in Liverpool and then across Britain. Her work and writings on public health played a key role in the passage of legislation that put health care decisions in the hands of local officials, not a centralized bureau, who were best equipped to deal with issues in their communities.

Nightingale continued her advocacy work until her death in 1910 at 90 years old, and her influence on the greater medical world is still felt today.