X

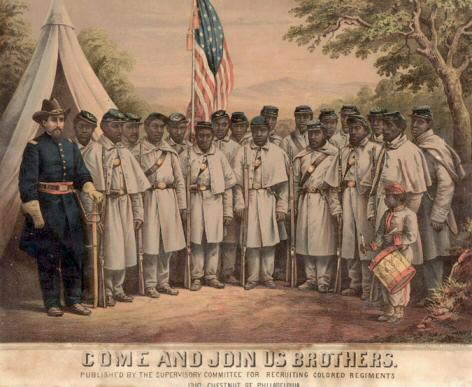

Photo: United States Colored Troops, Library of Congress.

In 2015 we celebrate Freedom by

commemorating the 150th anniversary of two events; the

end of the Civil War and passage of the 13th Amendment to the

Constitution and the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of

1965. African Americans played active,

even decisive roles in each event.

Freedom is not something given to African Americans; Freedom is

something African Americans have pursued for us all.

The beginning of the Civil War in 1861 gave African Americans hope; hope that the federal government would crush slavery along with the rebellion of slave-holding states. For most white Americans, the Civil War was a war to save the Union. For black Americans, it was a battle for freedom.

The North could not win the war and save the Union, let alone abolish slavery, without the active participation of African Americans. Tens of thousands of enslaved African Americans escaped bondage, denying their labor to the Confederacy and contributing to the region’s economic turmoil. Thousands of these served the Union army as laborers, stevedores, spies and cooks. By entering Union-held territory, they asserted their right to freedom and pressured the federal government to act. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, an estimated 90,000 freed slaves along with about 100,000 free blacks enlisted in the Union army’s newly formed United States Colored Troops.

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, responded to the need for additional military support and the demands of African Americans. Many hoped that Lincoln’s proclamation doomed slavery entirely. In fact, by the time of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery already had passed both houses of congress, been signed by Lincoln and was awaiting ratification by the states. The rebellion was crushed and slavery was being abolished.

Yet what would freedom mean? Economic independence? Freedom from fear? The right to vote? The U.S. Congress responded with a series of Constitutional amendments ending slavery, granting citizenship, and giving black men voting rights.

Photo: 107th U.S. Colored Infantry Band at Fort Corcoran. Arlington, Virginia, November 1865. Copyprint. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865. To protect the rights of newly freed people, Congress enacted two additional Constitutional amendments. The 14th Amendment (1868) guaranteed African Americans citizenship rights and promised that the federal government would enforce “equal protection of the laws.” The 15th Amendment (1870) stated that no one could be denied the right to vote based on “race, color or previous condition of servitude.” These amendments decreed that the federal government would protect individual rights if the states failed to do so.

Even with the Northern victory and the revision of state constitutions in the former Confederacy, nothing prevented individual states from reinstituting slavery at some future date. Ratified in December 1865, the 13th Amendment ended this threat by abolishing slavery “within the United States, or anywhere under their jurisdiction.”

But abolishing slavery was not nearly enough. The 14th Amendment, ratified by the states in July 1868, granted citizenship to all persons “born or naturalized in the United States” including former slaves. Further, it provided all citizens with “due process” and “equal protection under the laws.”

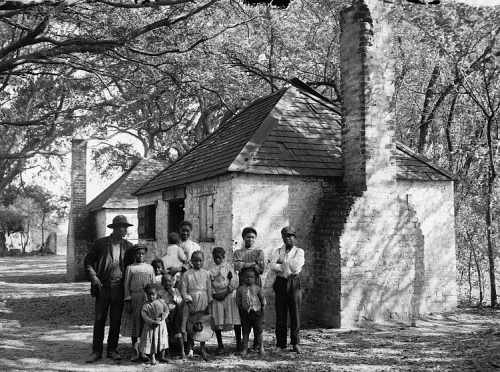

Photo: African American family in front of slave quarters. Library of Congress.

Finally, the states ratified the 15th Amendment in February 1870 forbidding federal and state governments from denying citizens the right to vote based on “race, color or previous conditions of servitude.” These amendments changed the political landscape. By 1872, 1,510 African Americans held office in the southern states. Eight black men served together in the U.S. Congress in 1875—a number that would not be matched until 1969.

The 15th Amendment promised but did not enforce equal voting rights. It did not prohibit the poll tax, literacy or other qualification tests or other means of restricting the vote. Soon, the former Confederate states enacted a series of laws and social practices effectively disenfranchising African Americans for the next hundred years. By the 1890s, southern states passed laws legally segregating black and white Americans. States excluded black voters by enacting literacy tests, poll taxes, elaborate registration systems, and whites-only Democratic Party primaries.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld these measures. In Mississippi, fewer than 9,000 of the 147,000 voting-age African Americans were registered after 1890. In Louisiana, where more than 130,000 black voters had been registered in 1896, the number had plummeted to 1,342 by 1904. It took another 95 years—3 generations of African America voters–before congress was willing to enforce equal voting rights for African Americans.

Photo: This photograph is part of a scrapbook that was compiled in 1956 and 1957 by Frances Albrier during her term as president of the San Francisco Chapter of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Frances Albrier Collection, ©Cox Studio.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is prefaced, “AN ACT to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution.” The legislation prohibited the discriminatory acts that kept black and poor white citizens from voting: literacy tests, poll taxes, hostile voter registration practices, violence and harassment. In addition, it required that nine states, mostly in the South, receive advance federal approval to change their election laws. (In 2013, the Supreme Court effectively removed this requirement.) Passing the original legislation was a cornerstone of the Civil Rights Movement.

As President Lyndon B. Johnson said, “The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro.”

The results were immediate and striking. The ranks of registered black voters exploded: for example, by 1969 60 percent of eligible black voters in Mississippi were registered. Nationwide, the number of black elected officials rose from 300 in 1965 to 1, 125 in 1969. In subsequent decades, the number grew to over 10,500.

The Voting Rights Act has been extended and revised several times. In 1975, at the urging of Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, it was expanded to explicitly include Hispanic and Native American voters. Thus, voting rights legislation promoted by civil rights activists 50 years ago has served to protect and even expand the rights of all Americans.

The much anticipated National Museum of African American History and Culture will come alive November 16th-18th during the Commemorate and Celebrate Freedom Event. The facade of the building will be illuminated with moving images in a spectacular display.

Learn more about the event here: http://s.si.edu/1Mj8d71.

Follow and join the conversation using the hashtag #IlluminateNMAAHC.

Post complied by Lanae S., Social Media Specialist, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Just a reminder that in 1965 we had to pass the Voting Rights Act to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, after 95 years of...

tinybunbuns liked this

tinybunbuns liked this  wolfs-strain liked this

wolfs-strain liked this  mountainmaven liked this

mountainmaven liked this  gabe00122 reblogged this from impressionsonmymind

gabe00122 reblogged this from impressionsonmymind  a-girl-cant-decide-on-a-name liked this

a-girl-cant-decide-on-a-name liked this  weareourowndevils liked this

weareourowndevils liked this  impressionsonmymind reblogged this from nmaahc

impressionsonmymind reblogged this from nmaahc  profkew reblogged this from nmaahc

profkew reblogged this from nmaahc  denisepostshere liked this

denisepostshere liked this  feedmybodytothemycelium reblogged this from nmaahc

feedmybodytothemycelium reblogged this from nmaahc The URL you requested could not be found.