New COVID-19 modeling: Social distancing is working in MN — but only if we keep it up

A new data analysis of the coronavirus outbreak nationwide suggests that Minnesota’s social distancing efforts might be paying off in its response to COVID-19 — but it also implies that even bigger outbreaks might lie ahead if those social distancing practices were to end.

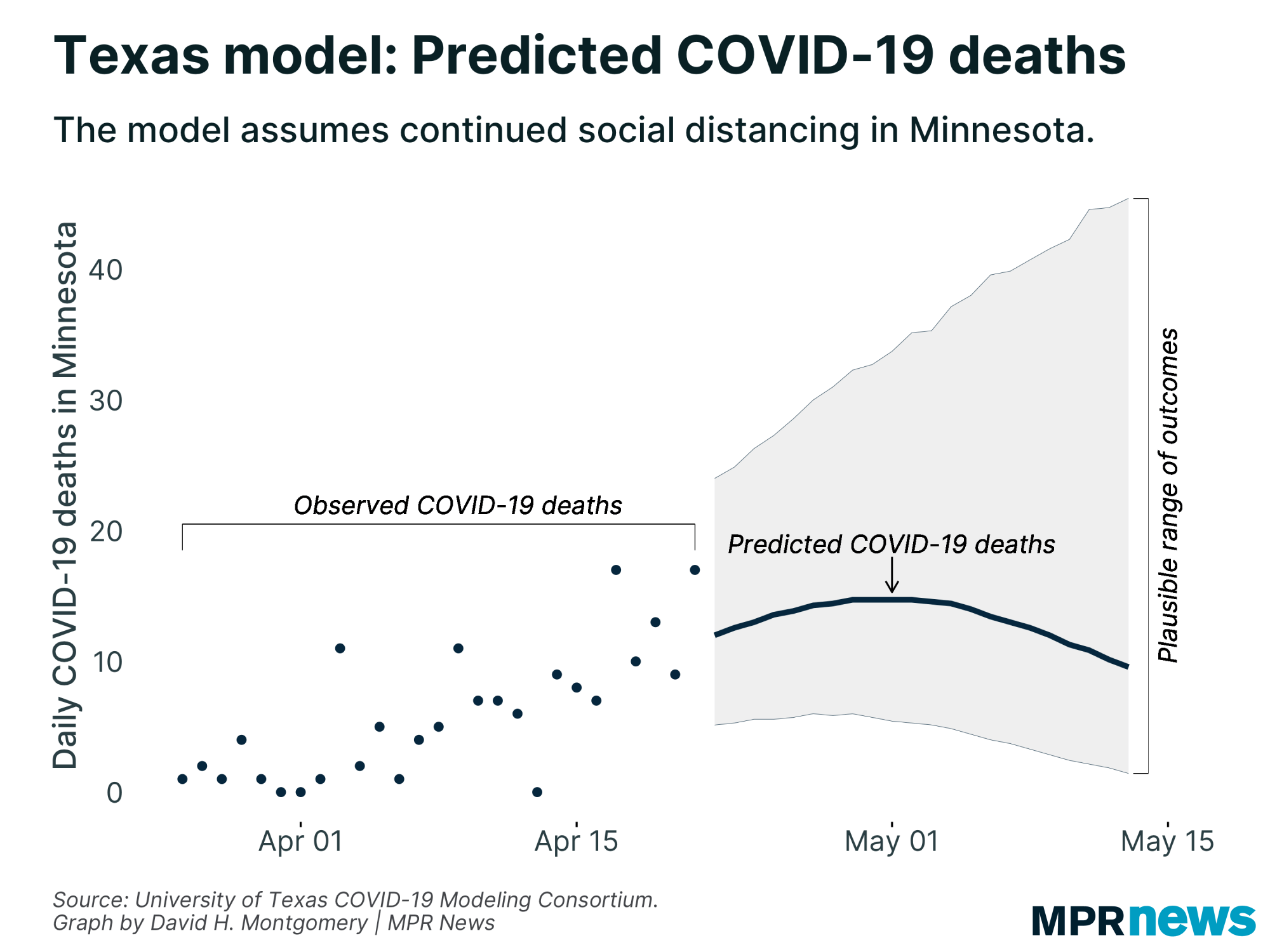

The new model of the outbreak was developed by researchers at the University of Texas. It’s one of many attempts by academics and government officials to use computer models to predict the course of COVID-19. Minnesota has its own model that state officials have consulted in their response to the pandemic. Because scientists still have a limited understanding of the new disease, each model uses different assumptions and different approaches in its predictions.

The work of the University of Texas COVID-19 Modeling Consortium is based on the correlation researchers observed between data that points to social distancing and a state’s number of COVID-19 deaths a few weeks later.

In other words, states where cellphone data showed people leaving their homes more often tended to have more COVID-19 deaths a few weeks later than states where that cellphone data shows people went out less. The time lag took into account their understanding that a person is most at risk of death a little more than three weeks after being infected with the virus.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

As of April 18, Minnesotans were about 20 percentage points more likely to stay home than they were before the outbreak, according to the aggregated cellphone location data published by SafeGraph the University of Texas researchers used to estimate social distancing. That’s the 15th highest increase in stay-at-home behavior in the country — and higher than all of Minnesota’s neighbors.

Based on the connection they made between Minnesotans’ cellphone movement and social distancing, as well as trends they observed in other states, the researchers estimate a 93 percent chance that Minnesota’s COVID-19 deaths will begin to decline in the next two weeks — and a 70 percent chance that will happen within the next week.

What happens if social distancing relaxes?

Those predictions depend on the public’s continued adherence to social distancing guidelines.

They’re based on an assumption that Minnesota continues to practice the same degree of social distancing over the next few weeks — even if deaths decline — that it has to this point.

“If social distancing restrictions are eased — or even if they're not eased, if people en masse decide that they're not going to abide by these guidelines — then certainly the projections of our model are out the window,” said James Scott, a professor of statistics and data science at the University of Texas at Austin, and a member of the team who built the model.

Minnesota’s stay-at-home order is scheduled to expire in just under two weeks — on May 4. Gov. Tim Walz has not yet announced what will happen when the order expires.

The Texas model makes its predictions three weeks out — through May 12, as of Thursday — so if Minnesota’s stay-at-home order is relaxed in May, the model would detect that decreased social distancing and likely predict more deaths two to three weeks down the road than it currently does.

Still, so far Scott said Minnesota has been ahead of the curve by employing social distancing guidelines — and then rules — relatively early in its COVID-19 outbreak.

“Texas and Minnesota are both examples of states that seemed to distance early” relative when their outbreaks began, Scott said. “All the pain that they've endured in terms of staying apart, not seeing their friends ... has undeniably saved lives, because they clearly got out ahead of things, compared to how New York and New Jersey were.”

Different models, vastly different outcomes

The University of Texas COVID-19 model is completely different from the model built by the University of Minnesota and Minnesota Department of Health — so different that they’re not really comparable.

They operate under two different assumptions about social distancing: The Texas model projects deaths two to three weeks out, on the assumption that social distancing will stay the same in that time period. The Minnesota model projects the outbreak into 2021 and assumes social distancing will relax at some point this spring or summer.

Given that, the Minnesota model forecasts the real peak of the outbreak to come this summer, once people begin interacting more — and, presumably, spreading the disease more quickly. That’s not a time frame or scenario that the Texas model even attempts to simulate.

Beyond those different assumptions, the models use completely different methods of assessment. Minnesota’s model is an epidemiological model based on estimates about the nature of COVID-19. The Texas model uses a “curve-fitting” approach that tries to detect a trend based on observed data.

The two approaches each have their strengths and weaknesses — and it’s not yet clear which approach will do a better job at predicting the course of COVID-19 in the state.

Minnesota’s epidemiological model, called an SEIR model because it uses details about the time periods in which people with a disease are Susceptible, Exposed, Infectious and Recovered, is based on decades of research into infectious diseases. But because COVID-19 is so new, many of the inputs — assumptions about the behavior of a disease — to an SEIR model are still unknown, leaving Minnesota’s model to rely on simulating hundreds of different estimates.

“We feel good about the model and the structure. It aligns well with the disease as we understand it right now,” Minnesota’s state health economist Stefan Gildemeister said earlier this month.

Curve-fitting models like the Texas model don’t take into account how diseases like COVID-19 function. Instead, it relies on data that reflects human behavior — which is easier to observe.

Scott, the Texas researcher, said curve-fitting is a good fit in this situation, given the uncertainty about inputs for SEIR models. But he acknowledged that no one knows which approach will prove most useful.

“If you have two models, both of which seem to be describing the data equally well and make very different forecasts about the future, that's a very difficult place to be in,” Scott said.

There are more than two COVID-19 models out there. Many states have developed their own models, with varying degrees of transparency, as have a number of academics.

Prominently cited modeling includes that of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, the White House coronavirus task force, and Imperial College in London. These models use different methods, different inputs, different time frames, and predict deaths from the pandemic an order of magnitude apart.

All of them, including Minnesota’s model, only predict harm caused by the disease itself, and not social or economic strain that arises as it spreads.

Walz and other policymakers have been relying primarily on Minnesota’s model to guide their understanding of the disease’s risk here, though they have acknowledged paying some attention to other models like the University of Washington’s.

Both the Texas and Minnesota models are being continually updated. Neither one yet accounts well for clusters of cases in a single place, such as a nursing home or a meatpacking plant like the JBS plant in Worthington that’s connected to dozens of cases in just the past few days.

Scott said his team in Texas is trying to better take into account the impacts of such outbreaks, and also to look at data on a more precise geographic level than entire states. A new version of Minnesota’s model is also being developed and may be released later this month.

COVID-19 in Minnesota

Health officials for weeks have been increasingly raising the alarm over the spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States. The disease is transmitted through respiratory droplets, coughs and sneezes, similar to the way the flu can spread.

Government and medical leaders are urging people to wash their hands frequently and well, refrain from touching their faces, cover their coughs, disinfect surfaces and avoid large crowds, all in an effort to curb the virus’ rapid spread.

The state of Minnesota has temporarily closed schools, while administrators work to determine next steps, and is requiring a temporary closure of all in-person dining at restaurants, bars and coffee shops, as well as theaters, gyms, yoga studios and other spaces in which people congregate in close proximity.