In the mid-1990s, a lab in Idaho found elevated levels of lead — 4.3 parts per million — in a Quincy farmer’s potatoes.

The farmer, Duke Giraud, was among several Northwest growers who combined to produce the potatoes for 80% of America’s French fries.

The finding eventually prompted another Quincy farmer, Tom Witte, to write a memo titled “Lead in Your French Fries?”

Witte’s 13-page memo alleged fertilizer makers had conspired with federal and state officials to hide hazardous metals in fertilizers. Those allegations — which were never proved — upset a large french fry producer in town, drew the ire of some farmers and alarmed the vice president of environmental affairs of the Northwest Food Processors Association, who feared it would cause “a large scale, unfounded food scare.”

Witte and Giraud have since died.

These events and others that sprouted in Quincy exposed something occurring in this rural Central Washington town and across the nation: Steel mills and other dirty industries were avoiding the high cost of disposing of their hazardous waste such as lead, arsenic and cadmium — metals that can cause health problems — by recycling it into fertilizer.

Hazardous waste from steel mills and other industries typically contains zinc, a plant nutrient. But often the recycled waste contains other manufacturing byproducts such as lead, cadmium and arsenic that are not beneficial to plants and can be harmful to people.

FILE -- Tom Witte and his sons were tested for toxins in their bodies. Different metals were found including aluminum, lead, cobalt and boron when their hair was tested. This liquid fertilizer tank, left on his farm in 1991, was tested and many hazardous chemicals were found including arsenic, aluminum, and copper to name a few.

Farmers unknowingly used fertilizer that contained nutrients as well as hazardous waste. Between 1990 and 1995, more than 600 companies nationwide sent 270 million pounds of toxic waste to farms and fertilizer companies, according to a 1998 report by the Environmental Working Group.

There were no standards or regulations, but the practice was legal.

After a Seattle Times investigation broke the news about what was happening, then-Gov. Gary Locke formed a task force to probe the matter. And in 1998, state lawmakers adopted new rules mirroring standards set in Canada.

Three years later the Environmental Protection Agency established some limits as well, but left regulation up to individual states.

In Washington, the state Department of Agriculture oversees the rules. Officials there say Washington is the only state in the country to have adopted Canadian standards, which regulators consider rigorous.

Those standards limit the amounts of heavy metals in fertilizers and require product registration, frequent sampling and testing, and biannual reporting. All fertilizers manufactured or sold in Washington are required to be registered with the Department of Agriculture.

Brent Perry, program manager for the Department of Agriculture’s fertilizer registration program, said the rules are working well and there are hardly any violations these days.

“I think in the last few years, maybe one or two products had to be removed because of heavy metals,” he said.

But not everyone agrees those standards are enough to safeguard the soil, food and public health.

Patty Martin, who helped uncover the practice of recycling hazardous waste into fertilizer while serving as Quincy’s mayor, said the standards were more about continuing to allow hazardous waste to be recycled into fertilizer than assuring safety to the environment and people.

“It was never about safety,” Martin said. “It was about giving the people an illusion of safety.”

Erika Schreder, science director at the environmental advocacy group Toxic Free Future, worries about the long-term effects of applying any hazardous waste to soil.

“It’s a huge concern, the idea that we can take toxic waste and spread it on farm fields,” Schreder said.

The standards

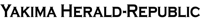

Washington regulates nine heavy metals in fertilizer: arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, mercury, molybdenum, lead, nickel, selenium and zinc.

A look at the limits of heavy metals used in fertilizers.

The EPA set standards for five heavy metals in fertilizer: cadmium, arsenic, lead, chromium and mercury. It sets those limits based on parts per million (ppm).

Washington’s regulations are based on application rates — a higher heavy metal content requires a lower application rate. These rates are broken down to pounds per acre.

For example, the annual limit per acre for arsenic is 0.297 pounds compared to 7.329 pounds of zinc, a nutrient metal that’s beneficial to crops.

“So just because a handful of stuff reads high, it may not be bad,” said Perry with the Department of Agriculture. “It has to be determined on application rate.”

That troubles Martin and Schreder.

A critical review

Schreder authored a 2001 report criticizing the standards. Her group was named the Washington Toxic Coalition at that time and the report was titled “Holding the Bag, How Toxic Waste in Fertilizer Fails Farmers and Gardeners.”

Canadian standards allow a doubling of background levels of heavy metals in soils over a 45-year period. Background levels refer to the rate that metals naturally occur in soil.

She said the state erred when it merely adopted the Canadian standards that were based on Canadian soil rather than determining background levels in Washington soils.

In her report, Schreder called the standards weak and took issue with regulations based on “application rates recommended by fertilizer manufacturers rather than the actual metals content of the fertilizer.”

Her group wanted hazardous waste banned from fertilizers altogether.

“We didn’t feel they were preventive enough,” Schreder recently said of the standards. “It didn’t make a lot of sense because it was allowing the accumulation of heavy metals in soil.”

She said the 45-year doubling standard wasn’t based on health guidelines.

“Once you spread toxic chemicals over land, it’s very difficult to take that back,” Schreder said. “You end up contaminating groundwater, drinking water.”

Often it takes years to learn of the harm industry practices can cause, she said.

As an example, Schreder points to Maine, where PFAS waste from paper mills was dumped on fields.

Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) are known as forever chemicals because they remain in the environment a long time. They have been linked to kidney and testicular cancer and other health problems.

“We continue to be concerned that waste taken from industry could cause serious contamination,” Schreder said. “We can’t always anticipate what chemicals will be present and highly problematic.”

Martin questions whether the 45-year standard was even studied.

Perry said that’s a question for Canadian regulators.

“From my point of view, the Legislature adopted that standard,” he said. “That’s the law. They adopted it.”

A report based on a Washington State University study submitted to the Legislature in 1998 did note concerns about cadmium buildup in soils.

The study probed four crops — lettuce, cucumbers, wheat and potatoes — for any uptake of lead, arsenic and cadmium.

“Cadmium levels in soils should be periodically monitored to ensure that levels do not become a concern in the future,” the report said.

In addition to other health problems, cadmium can cause cancer and kidney disease and damage lungs if inhaled, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

The 1998 report recommended the study be extended to other soil types before it could be applicable to a broad range of soil conditions.

The study found the transfer of lead and arsenic from soil to crop minimal compared to cadmium.

“Soils vary, uptake from plants vary,” Martin said. “There are so many unknowns. What possible combinations could happen in the soils? I don’t know that answer. I worry about that answer.”

Application rates

Martin wants to know what safeguards are in place to prevent growers from overapplying fertilizers containing heavy metals.

“If each application rate is set at the maximum, and you apply more than once (a year), you are moving faster to that doubling,” she said. “Who’s checking to make sure were not moving too fast to doubling?”

Perry, with the state Department of Agriculture, said manufacturers and suppliers are regulated and keep records of the amount they deliver to farms.

But that doesn’t mean a farmer cannot apply fertilizer products or double up by buying from more than one supplier.

Perry said suppliers typically sample soils to inform farmers of the amount of nutrients needed for a successful crop.

That usually prevents farmers from overapplying fertilizer, he said.

A truck passes The McGregor Co. — formerly Quincy Farm Chemicals — on Division Street East in Quincy on Aug. 31, 2023. Nearly 30 years ago, concerns about hazardous waste being recycled into fertilizers rocked this small, rural Central Washington city.

Since commercial fertilizer is expensive, Perry said, it wouldn’t make sense for a farmer to apply more than what's needed.

“If he applies more than he needs, the fertilizer bill goes up and he’s not making any more money,” Perry said.

There is a chance that a farmer could apply more than needed if the application rate wasn’t enough to bring his nutrient levels to good growing conditions.

In that case the farmer would be in violation of standards, but catching him wouldn’t be easy, Perry said.

“Yeah, he put on more than the recommended amount. Are we going to catch him? Probably not,” he said.

That’s partly because regulation is conducted mostly on the manufacturing and supply side of the industry. Lawmakers did not include soil sampling in the regulatory standards, Perry said.

But it’s unlikely a farmer would overapply, he said.

If a fertilizer was too weak, Perry said, it wouldn’t last on the market.

“It’s not a significant issue in our eyes,” Perry said. “We don’t have that big of an issue. It doesn’t need to be addressed.”

Public information

When Washington implemented standards in 1998, a handful of companies didn’t meet them, and some products were pulled from store shelves as a result.

Perry said violations dropped significantly after that and they're rare today.

“I’d say compliance is very good with the heavy metals,” he said.

Still, information about violations isn’t as easily accessible. Perry said he couldn’t say where violations were posted on the Department of Agriculture’s website.

Information about standards, products and fertilizer manufacturers registered to do business in Washington is available on the Department of Agriculture’s website. But information about heavy metals and other hazardous waste recycled into fertilizer is only available online — not on product labels.

Links to that information are also available on the Association of American Plant Food Control Officials’ (AAPFCO) website.

Fertilizer control officials from each state in the U.S. as well as Canada and Puerto Rico form AAPFCO. The organization’s mission is to establish uniformity in policy, standards and regulations of fertilizers.

AAPFCO posts state regulations and laws governing fertilizers online. Not every state has regulations or laws pertaining to fertilizers, however.

Only 14 states, including Washington, have laws and regulations pertaining to fertilizers posted on APPFCO’s website.

Twenty states are shown with laws but no regulations. Five states provided only regulations and 11 states provided neither.

AAPFCO President-Elect Mark LeBlanc says he believes most states have laws and regulations, though they may not be listed on his organization’s website.

“In some of these cases, if you go deep enough you can find a place they have a link to the law,” he said. “The program may not be very large or active, but I bet they have one.”

There is no real national database or clearing house for such information, he said.

“The states might share with AAPFCO, but it’s not like we’re trying to reach out to the public," LaBlanc said.

Although AAPFCO helps set policy and standards, it has no regulatory authority, he said.

“We create model bills, we approve nutrient rules, create model rules, model regulations and states decide on their own if they want to use those,” LeBlanc said. “We’re an association of control officials, but no state is obligated to follow what we do.”

• Editor's note: The Return to Quincy project is funded by TomKat Media, a film, television and media company founded by Tom Steyer and Kat Taylor to inspire creativity for the common good. Yakima Herald-Republic editors and reporters operate independently of our funders and maintain full editorial control over all project coverage.

(1) comment

Very informative-thank you. Did your investigation uncover any efforts to control this outrageous dumping of toxic metals into fertilizers by those profitting from it, rather than burdening farmers?

Log in to reply

Comments are now closed on this article.

Comments can only be made on article within the first 3 days of publication.