Adverse Childhood Experiences

Why Do Adverse Childhood Experiences Harm Us as Adults?

Understanding the mechanisms can help break the ACEs/health link.

Posted October 5, 2021 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Dysregulated stress resulting from Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) can continue to cause suffering in adulthood.

- Bringing stress to tolerable limits is a critical first step to healing and breaking the link between ACEs and harmful health outcomes.

- Reducing the suffering of adults affected by childhood adversity starts with regulating dysregulated pressure.

Since 1998, research has consistently demonstrated that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) predict adult health problems ranging from headaches and obesity to depression, anxiety, autoimmune disorders, heart disease, cancer, and sleep disorders. But how do events that occurred way back in childhood continue to affect our health so many years later? Understanding the mechanisms will later point us to ways to break the ACEs/adult health link.

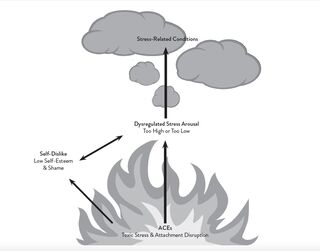

As the diagram shows, dysregulated stress is central to the ACEs/health outcomes relationship. Toxic stress in childhood can imprint and change the brain, biology, and sense of self in ways that affect adult well-being throughout life if not addressed. This is why the originator of ACEs research, Dr. Vincent Felitti, stated that we err to treat the smoke (stress-related conditions) without treating the flame (the underlying wounds from childhood that cause and maintain dysregulated stress). Dysregulated stress disrupts all systems of the body, including these.

Neurological Systems

Overwhelming stress in childhood, particularly during the brain’s tremendous growth spurt in the first three years of life, influences brain development in ways that keep the brain on high alert. During this growth spurt, traumatic experiences register not in the not-yet-developed (verbal/thinking) left brain, which will later recall memories consciously with words and reason, but in the relatively well-developed right brain.

With its strong connections to the emotional and survival regions of the brain, the right brain oversees the non-verbal, non-conscious processing of memories. It imprints childhood memories, which are experienced as images, sensations, visceral states (e.g., sick to the stomach; constriction of the throat; survival tendencies, such as tensing muscles and preparing to run away) and a strong feeling tone (a felt sense of nameless dread; a sense of inadequacy, depression, shame, anxiety, and so forth).

Even after the left brain fully develops, the right brain will remain dominant for the emotional processing of traumatic memories because the left brain goes off-line during overwhelming stress. It’s as though the brain says, “This is an emergency. There is no time to speak or reason with the threat. Right brain, take over.” If unaddressed, the patterns of danger and high alert imprinted in the right brain tend to persist, beneath the level of conscious awareness, over the lifetime.

Dysregulated Stress Hormones

Overwhelming stress can cause over-or under-secretion of stress hormones. (Under-secretion can result from chronic anxiety that exhausts the supply of stress hormones.) Cortisol is a major stress hormone that helps the body mobilize for fight or flight, and it is usually helpful in the short term. For example, cortisol converts protein to sugar to provide fuel for the stress response. Dysregulated cortisol, however, is linked to:

- Obesity

- Elevated blood sugar and diabetes

- Inflammation—a common culprit in a wide array of disorders

- Immune dysfunction–Too much cortisol suppresses immunity, leaving us vulnerable to colds, flu, and other infections. Too little cortisol allows the immune system to become over-reactive, putting us at risk for autoimmune disorders. Toxic stress in the early years can impair the immune system’s ability to distinguish friend from foe.

- Impaired brain and lung development resulting from the conversion of protein to sugar

- Disrupted sleep and mood

- Harmful changes in epigenomes and telomeres. The epigenome sits alongside DNA strands and determines gene expression, and therefore how the brain develops. Cortisol also shortens telomeres, the protective “cap” of the chromosome, disrupting proper brain development.

What Have We Learned So Far?

Toxic childhood stress can profoundly and continuously affect the adult’s brain and biology, and dysregulated stress is central to the ACEs/health outcome relationship. Reducing the suffering of adults affected by the wounds from childhood adversity starts with regulating dysregulated pressure—meaning we bring stress arousal levels within tolerable limits—neither too high nor too low. This allows the brain and body to restore physical health.

Regulating stress also enables the brain regions that were pushed off-line by overwhelming stress to come back on line— including the verbal, logical left brain and the areas that give us an integrated sense of self. This prepares the adult to process, settle, and rewire the inner wounds—the troubling memories imprinted in the first eighteen years of life.

This blog has mainly addressed how dysregulated stress from ACEs changes our brain and biology. Our next blog will explore how ACEs change our psychology in ways that maintain dysregulated stress. Ultimately, this understanding will help us apply the principles and skills that facilitate healing, well-being, and optimal functioning.

References

Schiraldi, G. R. (2021). The Adverse Childhood Experiences Recovery Workbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger