Editor's note: This is the second in a series of stories looking at conditions in the Monroe County Jail. The first story highlighted some of the problems and the history of jail discussions. This story takes a look issues related to mental health. The final two installments will take a deeper look at recidivism and programs designed to reduce reincarceration, and how long local court cases are taking to resolve.

A local jail built to detain defendants awaiting trial and the convicted serving time is burdened by being a detox center and mental health facility as well.

A doctor who used to service the Monroe County Jail once said, in regard to mental illness, it was one of the sickest jails he's seen. People with mental illness are consistently filtering in and out of the jail's "revolving door."

"The jail is the largest mental health facility in the county," jail commander Sam Crowe said recently as a mentally ill woman's wails echoed through a jail corridor.

As talk about a new multi-million-dollar jail project continues, community resources for people with mental health and substance abuse issues are too few and lack funding. It's these services that advocates and studies agree help people get back on their feet and avoid the system altogether. Monroe County has some resources and specialty courts, but many people still fall through the cracks as addressing mental health remains a significant community issue.

'It was outdated when they built it': Why Monroe County is 'past due' on a new jail

Monroe County jail committee struggles to make progress without quorum

People with mental illness have a much higher risk of incarceration and criminal justice system involvement, according to a Monroe County incarceration and criminal justice system study. National studies have found these individuals often are disproportionately represented in jails.

Falling into the cycle

Tammie Eppley, anadministrative director at Centerstone, recalls a person the Stride Center helped to avoid incarceration.

Police dropped the person off after they were evicted from their housing and found themselves experiencing a mental health crisis. They passed out, and the center took them to the hospital where the person stayed for three weeks. Then they went to the Stride Center where they received help, including with taking their prescribed medication. Now, she said they've regained possession of their car, have a stable job and signed a lease for an apartment.

Without the center, Eppley said the person probably would have ended up in jail — making it that much harder to get their life back on track. She recounted multiple stories of people with mental health issues who ended up walking through the center's doors instead of being booked into jail.

"Almost all the folks that have come in have a substance use or mental health disorder," she said.

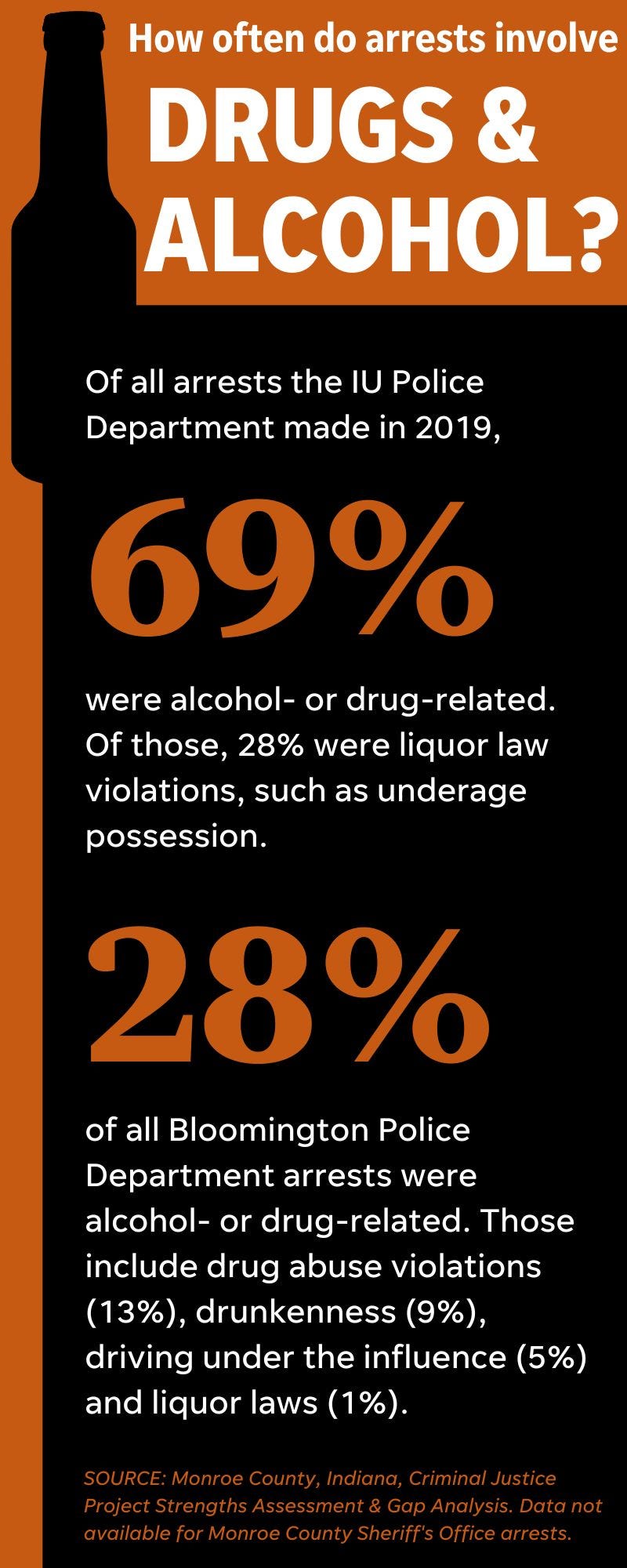

People incarcerated in jails are five times more likely to have a serious mental illness than the general public, according to Prison Policy Initiative analysis. In a U.S. Department of Justice 2017 report, 63% of surveyed jail inmates typically met the criteria for substance abuse or dependence.

"Incarceration itself can bring out or can aggravate mental health problems," said Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative. "So people who are going into the jail might come out with a more serious problem they had actually going in."

A Strengths Assessment and Gaps Analysis commissioned by the county reported the jail does not gather adequate data about inmates to know what percentage have substance use or mental disorders, but states, "Individuals both within and outside the criminal justice system in Monroe County estimate that 75–80% of the individuals in MCCC (Monroe County Correctional Center) at any given time have mental illness and/or SUD (Substance Use Disorder.)" The study states that in 2018, inmates accused of possessing controlled substances spent the equivalent of 11,214 days in the local jail. Those accused of public intoxication spent 4,173 days.

Once someone loses their access to reliable health care, they're placed in a really precarious position. That's when they're subject to bouncing in and out of criminal justice."

About one in five adults in the U.S. were living with a mental illness in 2020, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. In Indiana, 114,044 people were reported to be in 284 mental health treatment facilities, according to 2020 data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Miriam Northcutt Bohmert, Indiana University criminal justice associate professor, said many people fall into trouble when they don't have access to mental health care, including medications or counseling. This is further complicated when they turn to illegal street drugs to self-medicate, she said. When a person is both unhoused and mentally ill, Bohmert said, they are more visible to police. The process a person goes through to address those issues is on display, instead of being dealt with privately in a home.

"Once someone loses their access to reliable health care, they're placed in a really precarious position," she said. "That's when they're subject to bouncing in and out of criminal justice."

When someone is in and out of jail, in and out of treatment, Bohmert said it interrupts their life and continuity of care. Pre-existing mental health conditions tend to get worse, including experiencing more trauma.

"When you try to turn those facilities into mental health facilities, you're really kind of working from a much more difficult position than if you focus on the community," she said.

Current mental health conditions in the jail

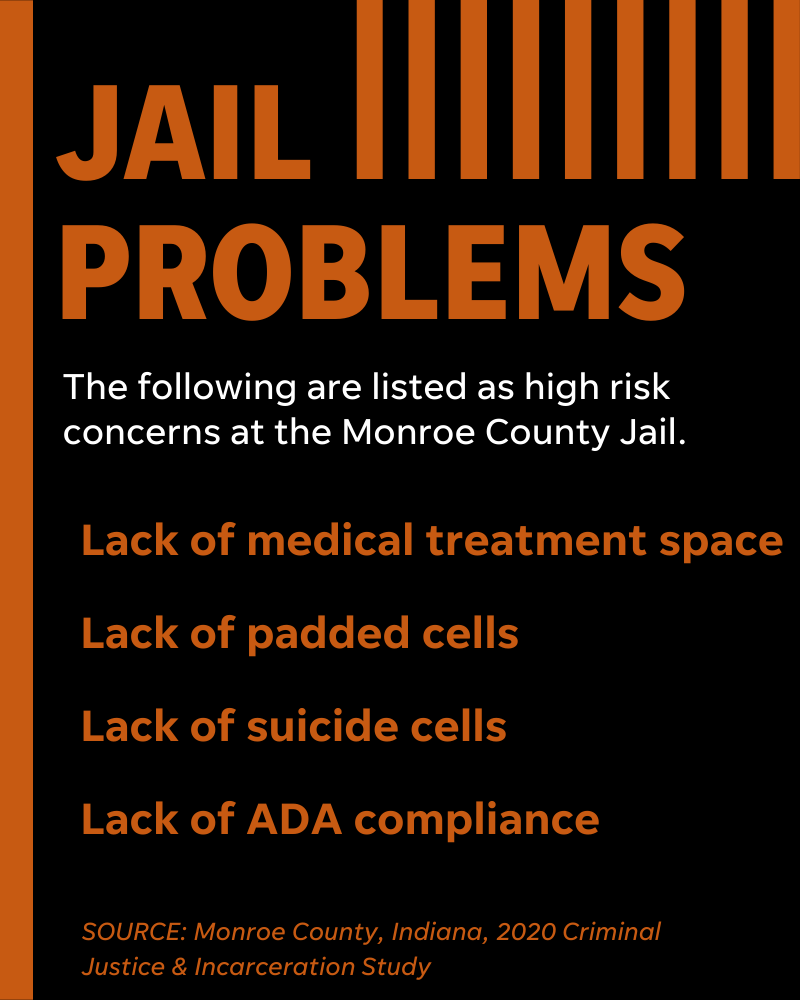

The Monroe County Jail is operating with its "hands tied," Crowe said. They don't have enough beds, program space or staff to help people — and that's without dealing with mental illness. The 254-page study of the Monroe County Jail and justice system backs him up.

Jails are required to protect their inmates from present and future harm, including mental health risks, the study says. Crowe said he and his staff do their best to help people in their facility since they will eventually be released back into the community.

In 2017, the jail renovated what was a file storage room into a new mental health dorm with a shower area and four new cells, housing up to seven inmates. The jail's surveillance also was updated as video surveillance was key for the new addition. Where were people housed before this was built? They fell into general population areas, as they still do, or were placed in a medical isolation cell.

In its 2022 inspection report, the jail had multiple staff members available to treat inmates, including a nurse supervisor, a few fulltime LPNs and a psychiatric nurse practitioner. Available provider hours have increased due to more demand during the pandemic. However, Crowe said that time is still not enough to address inmates' growing needs.

After 36 years, some say it's time for a new jail. County officials have surface level conversations in meetings now and then, and that is when those meetings aren't canceled. Crowe says a new jai is long overdue. Many taxpayers scoff that it's too expensive as other advocates say it won't fix the crux of the problem of why people end up in jail.

How did we get here?

Jails have become major mental health facilities because of the lack of community resource funding when asylums and many psychiatric hospitals shut down decades ago. Many people now don't have access to the level of mental health services available 30 years ago, Bertram said.

"Everyone was promised that there were going to be new community-based mental health facilities to replace those big asylums," she said. "That never happened."

In 1989, advocates said people with mental illnesses were ending up either in jail, homeless or both if they could not provide for themselves or find a sufficient program. The H-T reported in 1992 that Indiana was struggling to address the needs of people with mental health problems. One local community center counselor called it "the Dark Ages." Another public health research group said the state was "moving backwards."

There was and still is a surplus of people trying to use a deficit of services. Complacency and a lack of funds were said to dictate the future of mental health care in Indiana. Not much has changed.

Getting back on their feet

Bloomington has resources and infrastructure to help those who need it. While everyone says it's not enough, local service agencies say it is enough for many people in surrounding counties to migrate to Bloomington because they can receive more support.

Multiple studies and advocates say the best solution to solve the surplus of mentally ill people winding up in jails is through community-based programs. That way, they receive care and support to prevent incarceration altogether.

"You can connect somebody to mental health services in jail," Bertram said. "But that means nothing if the person leaves custody and has no ability to access mental health services."

When someone ends up in jail, Bohmert said they need help stabilizing and learning healthy coping mechanisms through programming. However, it is critical for services to be available when someone leaves, so they don't lose the progress they made.

Since its opening in 2020, the Stride Center has had 1,752 visits, some of which have diverted people going through a crisis from ending up in jail. Clients can walk in or police may drop them off, which accounts for 30% of their guests. People can come back and find resources suited for their situation. Sometimes, Eppley said, people aren't ready to launch themselves into substance abuse treatment, job interviews, emotional support and housing help. The center looks to build rapport and trust, she said, so people come back when they are ready. About 62% of them return.

The center is right down the alley from the jail, which Eppley said has led some people to walk straight there after they're released. Of the people who have walked through their doors, 70% were have been in the justice system.

The Stride Center is open every day all year, including holidays, which Eppley said fulfills a community need. Many local shelters and charities are closed on weekends. In the next few months, Eppley said the center is launching a new mobile crisis vehicle, servicing the area around Bloomington.

More:Staffing, safety and funding issues to close Shalom Center on weekends

New Leaf New Life connects people to services and resources inside and out of the jail to help them mitigate challenges. The agency offers programs, such as the ability for inmates to read to their children, and communication for treatment and referrals. Prior to the pandemic, the center had more programming within the jail.

"We really drive our services based on what you are experiencing, the challenges, what they need or what they want," board member Donyel Byrd said.

Monroe County has multiple specialty courts to help reduce recidivism and better target the problem of repeat incarceration. One is Judge Mary Ellen Diekhoff's mental health court.

A person charged with a crime can be referred to this court if they seem like they could fulfill a set of requirements and benefit from it. Once evaluated by the Mental Health Court Team and accepted, the person meets with a case manager, is checked out for medication and goes to court weekly. Over time, the court check-ups grow longer apart as the person progresses. All participants have to plead guilty in court, however, with completion of the program. Diekhoff said those charges are eventually dismissed.

"The goal is to address people's issues, not to just address whatever crime it is that brought them into that system to begin with," she said.

These courts are one of the most effective things the Monroe County criminal justice system does, Diekhoff said. Because they focus on people's issues, she said they see improvement over time. The people they work with tend to get sober, get jobs and get their family back.

"Mental health court has done a tremendous job of realizing the complexity of their clients," Northcutt Bohmert said.

Not every road to recovery is perfect, Bohmert said, but what could be considered a step back in some cases could be a success in this court. Diekhoff said they emphasize "progress, not perfection."

Will a new jail fix the problem?

Probably not.

"A new jail is not going to solve the fact that there are a lot of people in Bloomington that are struggling with mental illness," Bertram said. "It just can't help with that."

Many say building a new jail will not fix the reasons why people end up there. It won't fix the lack of affordable housing, decent-paying jobs or mental health services.

The county needs to look at its gaps of treatment centers and services, Bertram said. Those issues must to be addressed instead of assuming a new jail is a fix-all. When a community's healthcare services are improved and more accessible, she said a lower number of people ideally will end up in jail.

Talk of the new jail gives Bohmert pause. While the current jail may need better facilities, she said adding more beds will just result in more people filling them. Overcapacity is an issue, she said; however, judges may deal with people in their court differently if there are two open beds compared to 200. Diekhoff declined to indicate whether jail capacity is a factor in her decisions. Officials must find more creative ways to avoid incarceration and be thoughtful of how they build the space, Bohmert said.

While the intentions are typically well-meaning, Byrd said many fall into the ideology that community safety is created through the incarceration of people who are considered to be discomforting, reckless, under the influence or mentally ill.

When we use our criminal legal system as our mental health treatment, our substance use treatment, our behavior management, we are not creating additional safety. We're compounding the problem for future generations.

"If we want to reduce recidivism, if we want to reduce the numbers in our jail population, it would seem to me that the county's dollars could be more effectively spent providing folks the support they need to stay out of jail and prevent them, of course, from entering incarceration," she said.

Byrd understands the "unsanitary" and "barbaric" conditions of the jail, but she doesn't support building a new one because "it just kicks the can down the road." Instead, she said officials should look at their opportunity to build a mental health and substance abuse disorder facility to better address the root causes of why many people are incarcerated.

Instead of relying on the jail to be the place to go when there is nowhere to go, she said the county and city should focus on providing mental health and substance use treatment. People should not have to be incarcerated to receive help, she said.

"When we use our criminal legal system as our mental health treatment, our substance use treatment, our behavior management, we are not creating additional safety," she said. "We're compounding the problem for future generations."

Cate Charron is a former intern for The Herald-Times. You can reach her on Twitter at @CateCharron.