history

LIVING OFF THE LAND: THE STORY OF THE YAQO’N AND THEIR ANCESTRAL HOMELAND

Where the Yaquina River widens to become Yaquina Bay on Oregon’s central coast, an unnamed 400-acre peninsula lies between King and McCaffery Sloughs. It was here — and in the surrounding area — that a tribe known as the Yaqo’n made their home within the Yaquina watershed.

The Yaqo’n lived since time immemorial in the region between Cape Foulweather and Beaver Creek. They moved on foot and inhabited terrain that was inland enough to provide protection from the persistent coastal winds. The shores of the peninsula were lined with small, delicious oysters, and the river flush with salmon. Considered hunter-gatherers, the Yaqo’n didn’t possess guns or horses and flourished through their connection to the land and waters that teemed with life.

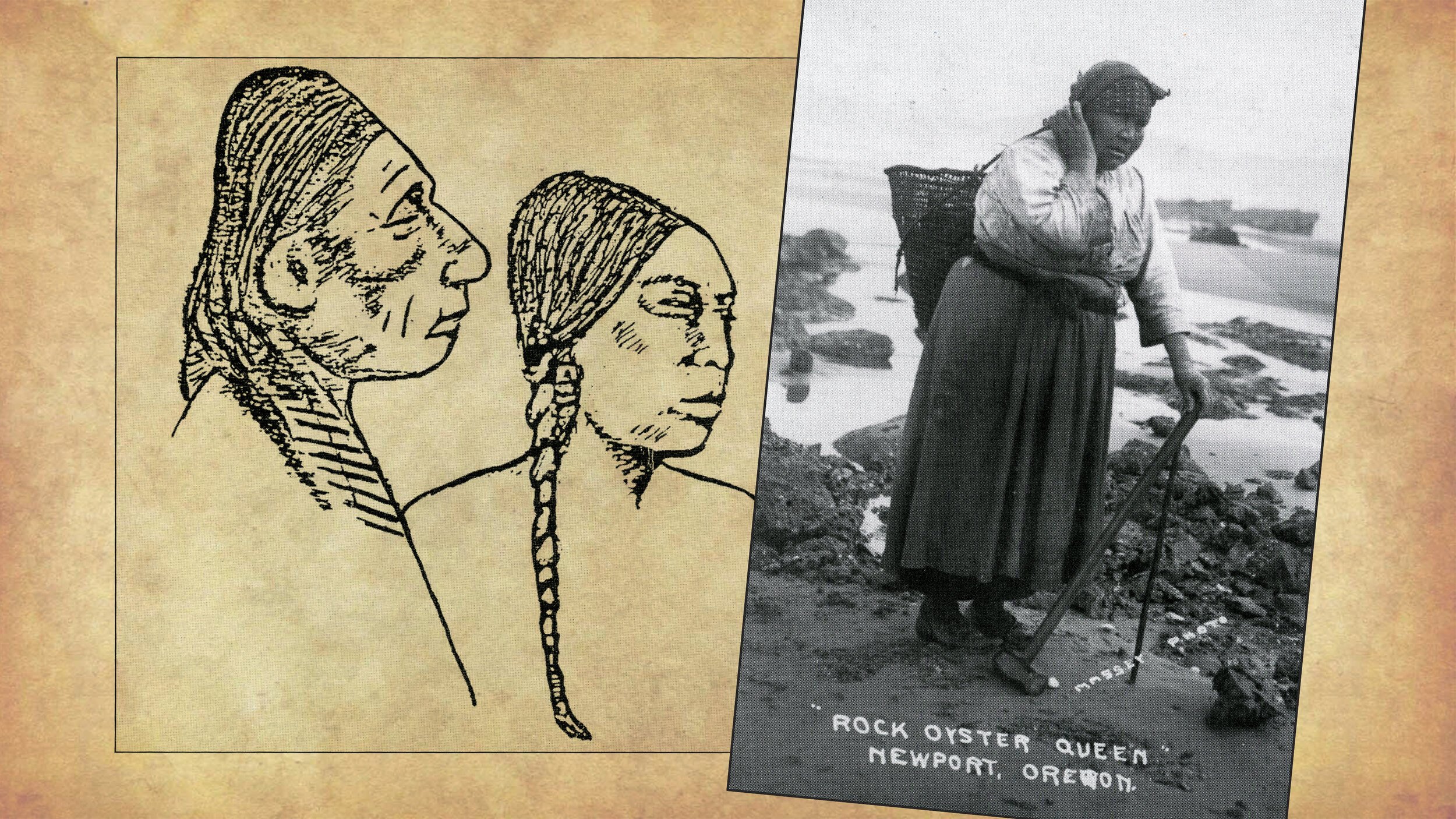

This tribe was known by European colonists as “flatheads” due to their tradition of intentionally flattening the shape of the heads of the upper class. They believed this unique profile would distinguish them from lower classes in the afterlife, securing their place in the next world. So, when upper class Yaqo’n babies were born, wooden pressers were placed on their head for six months to flatten their foreheads.

Prior to European contact, the Yaqo’n shared the land with plentiful wildlife and their native neighbors. To the south, the Alsea lived along the coastal shores and upriver along the present-day Alsea River, and the Tillamook lived to the north. Ethnographers estimate that as many as 700 Yaqo’n people flourished in the region.

REMOVAL AND ASSIMILATION

European fur trappers and early colonists carried diseases that decimated Oregon’s first peoples, who had developed no natural immunities. By the late 1700s, smallpox, measles, tuberculosis, and other diseases had claimed eighty percent of Oregon’s native people, the Yaqo’n among them. In 1820, due to a tragic case of mistaken identity, the Hudson Bay Company, seeking retribution for the death of two trappers and determined to teach a lesson, massacred many of the surviving Yaqo’n. Forest fires further decreased tribal numbers and by the end of 1849, approximately 80 Yaqo’n people remained.

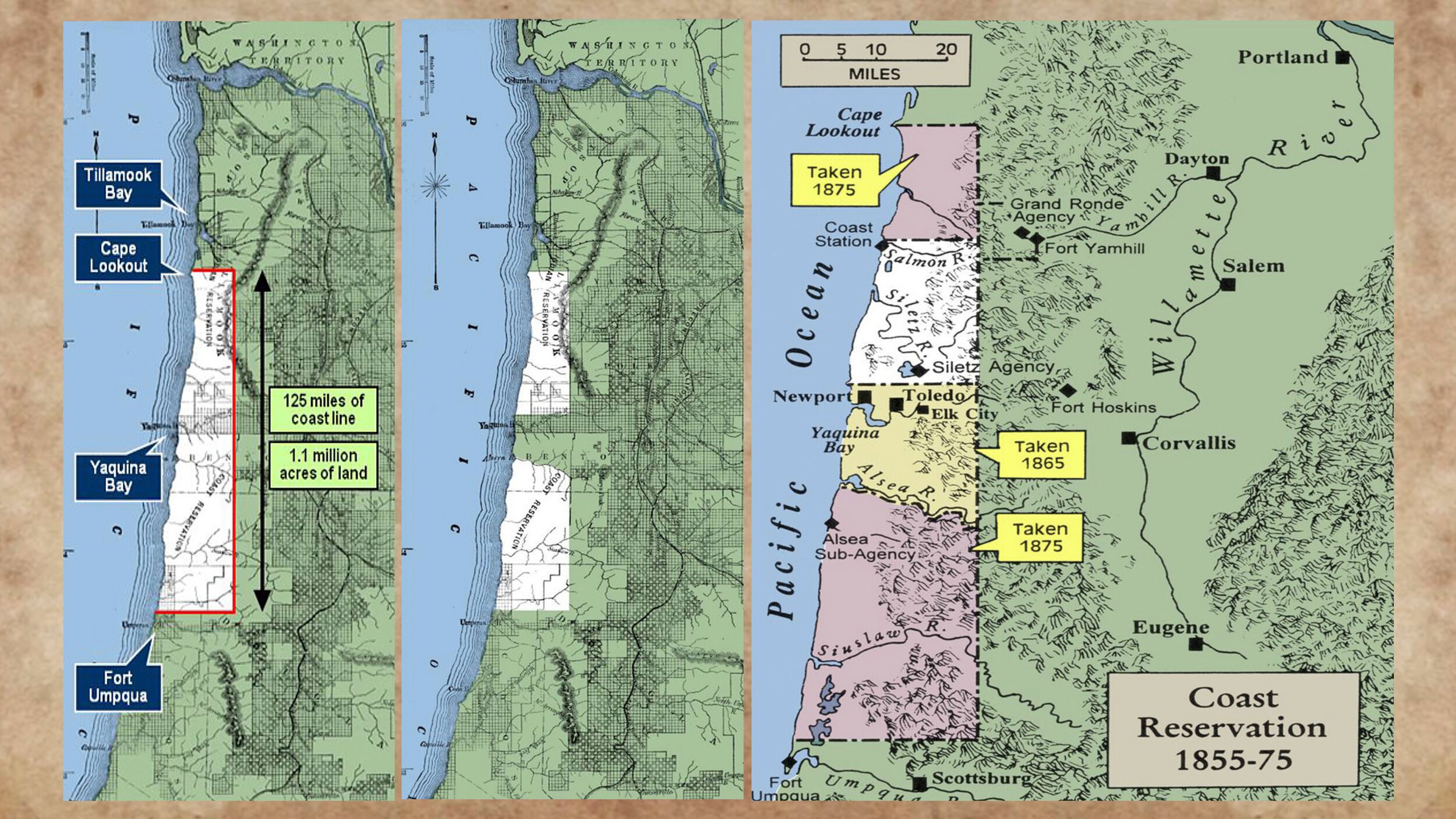

During westward expansion of the growing nation, the United States government formed the Siletz Reservation in 1855. Based on federal government promises and treaties never ratified, representatives from five tribes met on Yaquina Bay and signed away their rights to these ancestral lands. Two thousand seven hundred indigenous people from 27 different tribes and bands, some from as far away as southern Washington and northern California, were forcibly relocated onto the reservation. Its land area consisted of 102 miles of coastline, ranging from Cape Lookout in the north to an area between the Siuslaw and Umpqua Rivers in the south, and 20 miles inland.

Indigenous people who were moved onto the reservation from other areas – northern California to southern Washington, and west of the Cascade Mountains - were told to leave food, clothing, and shelter behind. Many people died along the way, and when they arrived, the white man’s promises were again proven to be unworthy. There were no houses waiting for them, nor was there any food, save for weevil-infested flour. Many more died that first winter on the reservation.

Initially, the Coast Range served as a natural barrier separating the reservation from colonists who began farming the fertile Willamette Valley. While relocating the native population was convenient for these recent immigrants, each tribe had its own distinct culture, customs and ways of life. In this new paradigm, they were all forced to live together as a confederation of tribes and “assimilate” the colonist’s ways of living.

Governmental policy turned to cultural genocide on several fronts. Native people were held captive on the reservation, and when they tried to go home, they were chased down and forced to return, or were simply killed on site. The military was replaced by missionaries in the 1870’s, who were resolved to indoctrinate the Yaqo’n and others in their religion, education, and customs. Boarding schools were built, and children were taken from their families, forced to cut their hair and wear the clothing that was given to them, and beaten if caught speaking in their native language. Whipping posts were used whenever natives followed banned tribal practices, and other atrocities were conducted to try and force the native people to abandon their traditional way of life.

In1861, a Yaqo’n woman shared the location of a rich supply of native oysters near McCaffery Slough with a soldier. Soon, white men began harvesting and selling the small, delicious mollusks found only in Yaquina waters, and they became an immediate hit in San Francisco, sparking interest in the area. Without a strong military presence or ratification of the tribal treaty, colonists continually trespassed on reservation land in pursuit of oysters and fortune. The first European settlement on the Yaquina River, named Oysterville, was near what is now known as Poole Slough. Native women worked sorting oysters for the immigrants who harvested them. Economic incentive and political pressure mounted to remove the Yaquina River and its watershed from the reservation.

The Yaqo’n, being from the area, had not needed to move from another region, as had so many other native people who found themselves living on the Siletz Reservation. Instead, they remained around Yaquina Bay, living in homes and wearing clothing as assimilation policies dictated. They traveled two well-established trails from the Yaquina River to the community of Siletz on a regular basis. Yet, the pressure to open up the reservation to white settlers was strong. President Andrew Johnson’s Secretary of the Interior, James Harlan, told him that the Yaquina River area was no longer occupied or desired by natives, so the government appropriated $16,500 to “buy” the Yaquina River and its watershed. In 1865, the Yaquina watershed was taken back by the federal government, and a strip of land 25 miles wide was carved from the center of the reservation and opened to the tide of advancing colonists.

It wasn’t long before the rest of the reservation was taken back by the United States government. In 1875, the remaining Alsea tract, the Siuslaw tract, and the Nestucca tract were removed from the Siletz Reservation. Now all native people who were not living in the community of Siletz were forced to leave their homes (or risk being killed) and move onto the 225,000 acres that remained of the original 1.1 million acre Siletz Reservation.

self determination

It took 27 years, but the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians fought hard and won back their sovereign rights in 1977. They were the second terminated tribe in the country to regain those rights. The Bureau of Land Management gave back 3,600 acres of forested lands to the tribe, and the City of Siletz restored tribal agency lands. The Siletz Tribe continues to work diligently to restore their land base. By the 1980’s, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians was running their own school emphasizing language, culture, and history; a health clinic; substance use prevention programs; and cultural and natural resource departments. Today, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians manage the Chinook Winds Casino and Hotel, and give charitably to communities in which tribal members live.

THE BIRTH OF NEWPORT AND YAQUINA CITY

In 1866, Sam Case and Dr. J.R. Bayley opened a large hotel on the north side of Yaquina Bay at the site of today’s U.S. Coast Guard station and named their settlement Newport. Guests at the hotel made the arduous wagon journey from the Willamette Valley to visit the seashore. In less than a year, Newport had saloons, stores and more hotels. Sacks of oysters could be harvested with tongs along the shores of the bay without waiting for low tide.

By 1870, sawmills had sprung up around the bay and white colonists had logged conifers some ten feet in diameter from the area. Homes, gardens, docks and a school were built on the peninsula near its largest slough. Commerce grew in the newly settled area.

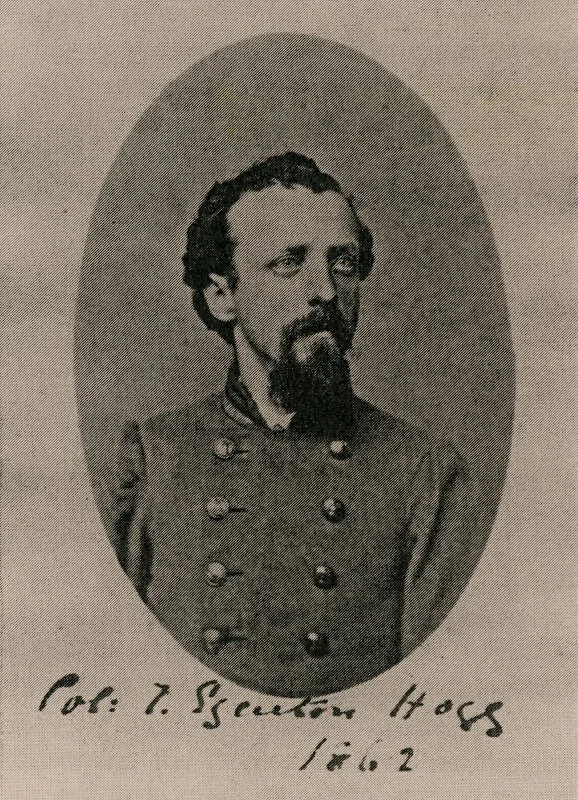

A San Francisco entrepreneur, Colonel T. Egenton Hogg, aspired to lay tracks from Corvallis to the coast, making it the terminus of a transcontinental railroad. Hogg amassed a bevy of investors from as far away as New York and England. Wallace Nash, a contemporary of Charles Darwin and co-founder of Oregon State University, was Hogg’s lawyer. In 1877, Hogg offered Newport’s residents $50,000 for the waterfront, which they summarily rejected. Undaunted, Hogg turned his sights four miles upriver, and in 1882, formed his own town where Sawyer’s Landing is now located, naming it Yaquina City.

The January 8, 1883 edition of the New York Times extolled the benefits of Yaquina Bay, reading: “… a sunken reef three quarters of a mile from the coastline provides safe entrance even in storms. This is a peculiar advantage which no other harbor in the world possesses and is of the highest value … neat homes dot the river.”

In 1884, West Yaquina was platted on the peninsula directly across the bay from Yaquina City, promising future home sites for wealthy New York investors in Hogg’s railroad – a Martha’s Vineyard of the west. New homes and a school were built. A ferry service ran between West Yaquina, Yaquina City and Newport.

Hogg’s railroad provided daily train service to the coast by mid-1885, lurching from Corvallis to Yaquina City. His town quickly grew to more than 1,500 residents and boasted “good school and church privileges, a fine hotel, a sawmill, three salmon canneries, the only banking house in the county outside Corvallis, a shipyard, customs house, telegraph office, large warehouse and docks for handling freight, a railway depot and yard with the company’s machine shops …” While Corvallis was a dry town, Yaquina City boasted a saloon on a barge docked in the river.

In 1888, Yaquina Bay had 144 ships entering and leaving - it was “the FedEx of the day.” Highly prized Oregon cargo included Yaquina oysters, salmon, apples, pigeons, chittum bark, cheese, granite, and wheat. Hogg purchased a 231-foot ocean going steamer, named it the Yaquina City, and was shipping products to San Francisco in a record 37 hours. But in December 1887, the Yaquina City sunk crossing the Yaquina Bay bar. Hogg immediately bought a second ship, the Yaquina Bay, but it also wrecked and sank. The back-to-back losses bankrupted Hogg, and ownership of his railroad passed to the Southern Pacific Railroad company

Federal investment in the jetties at the entrance to Yaquina Bay allowed greater shipping opportunities, with 522 vessels visiting the harbor between 1912 and 1915. Newport continued to grow while Yaquina City began to dwindle. The popular native oysters were over-harvested, vanishing from the Yaquina watershed.

WORLD WAR I - PRIME TIMBER FOR A NATIONAL CAUSE

WWI broke out in Europe in 1914, and by 1917, the United States had entered the war. Air supremacy was crucial to the ultimate victor, so Congress appropriated $1 billion to fund wartime aircraft production.

Sitka spruce is tall, strong, and lightweight, perfect for early aircraft manufacturing. Oregon and Washington had the largest stands of Sitka spruce growing along the coast, with some over 300 feet tall. However, loggers were unionizing, and lumber barons were discontented. General Pershing called up retired Commanding Brigadier General Brice Disque to “manage” the lumber industry, the result of which was the Spruce Production Division, also known as the Logger/Soldier Brigade, the first and only time this has happened in the country’s history.

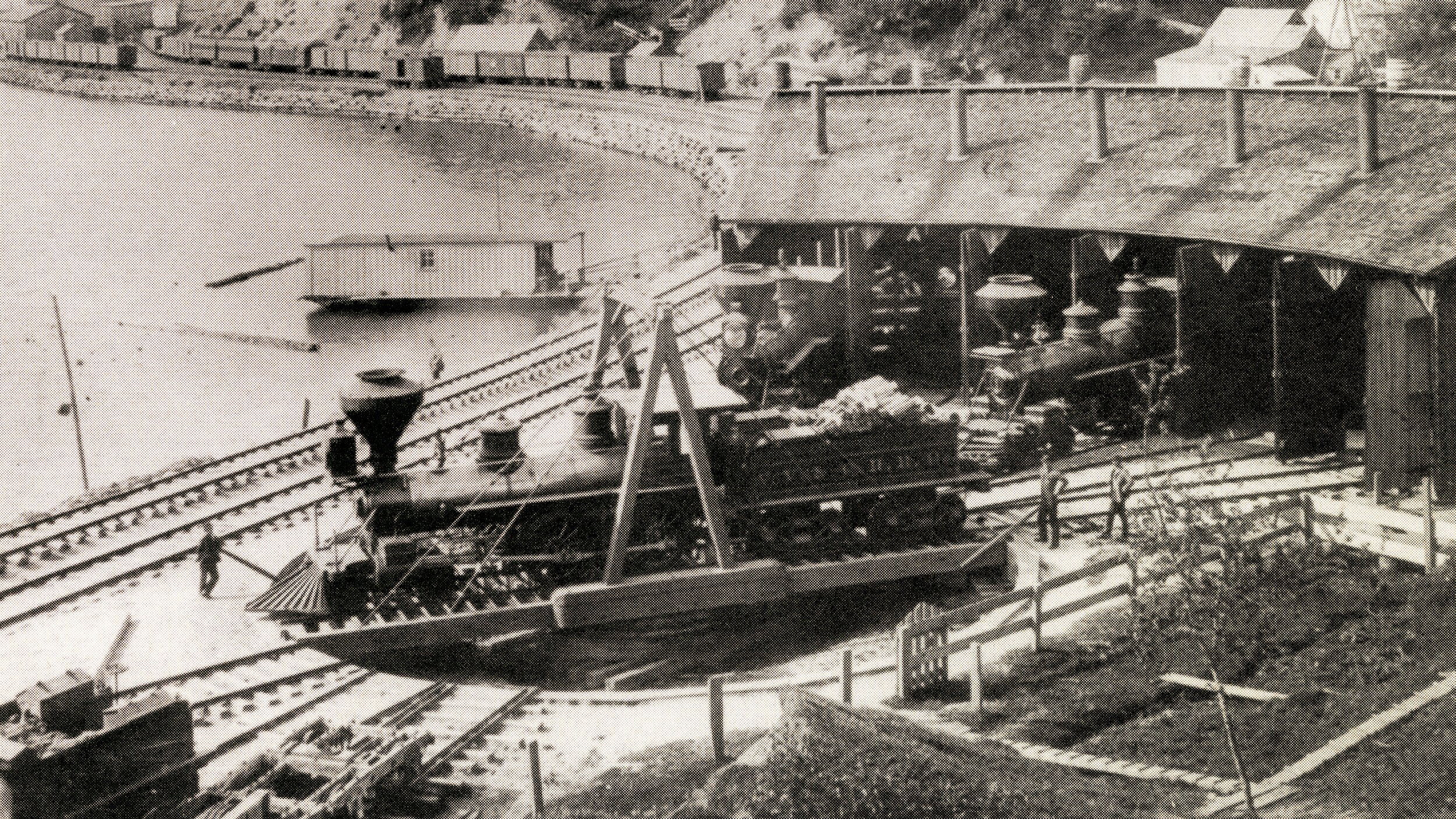

The Yaquina railroad station in 1912. Across the river is West Yaquina, within today’s Yakona Nature Preserve. Thirty-five thousand workers were drafted into the brigade to provide the necessary labor force, greatly increasing the efficiency of felling timber. Eleven railroads were built in the Pacific Northwest, three of them terminating in the Yaquina Bay area. Yaquina City came alive again, this time with soldiers.

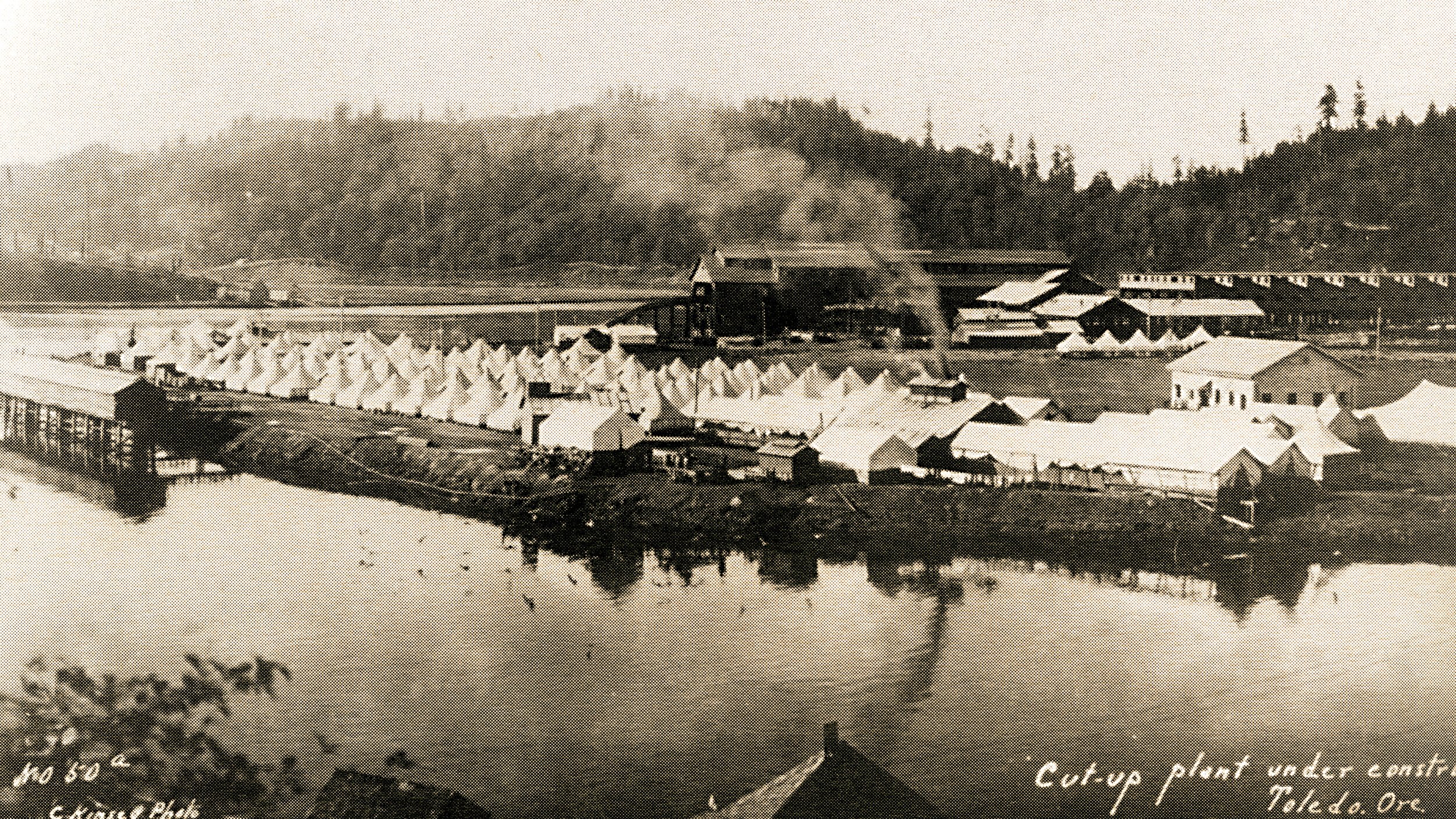

Many mills were built, as well. By spring of 1918, 10 million monthly board feet of lumber were under production. The summer of 1918 also saw the start of construction on a new lumber mill in Toledo, upriver from Yaquina City and West Yaquina. The spruce mill employed two shifts of 1,500 workers – 3,000 per day.

The Armistice ending WWI was signed 30 days before the mill became operational, and the military’s intense need for high-grade lumber evaporated. By war’s end, Allied Forces had built 10,000 airplanes, six times as many aircraft as Germany, dominating airspace and winning the war.

The railroad tracks laid to access prime spruce during WWI were sold to private interests and logging became the backbone of the local economy. Around 1934, truck logging proved more flexible and practicable. As a result, train service to Yaquina City ceased and the precarious railroad tracks from Toledo to Yaquina City were removed. Once considered the prosperous “San Francisco of the North,” Yaquina City was soon a ghost town.

PRESERVING THE LEGACY AND SECURING THE FUTURE

A big bend in the Yaquina River frames an isolated peninsula that lies between King and McCaffery Sloughs. Multiple small, privately-owned parcels, handed down through generations since the early 20th century, comprised much of this peninsula. Lack of access to these parcels resulted in large areas of forest untouched by modern logging, leaving extensive areas of mature, native ecosystems that flourished in its absence. However, the peninsula and surrounding areas were zoned Timber Conservation in 1970, and commercial timber harvesting resumed at a rapid pace.

Bill and JoAnn Barton learned of the peninsula and its rich history in 2008. Their first purchase five years later included 77 acres that crowned the peninsula — 47 acres of which had been commercially harvested two years earlier. To date, the founders of the Yakona Nature Preserve have acquired over 340 acres of land – including the majority of the vacated towns of West Yaquina and Parker’s Addition – and made substantial improvements on the peninsula, including abatement of invasive species; replanting a 47-acre clear cut with native trees, shrubs, grasses and flowers; and construction of four bridges and nearly seven miles of hiking trails.

These purchases are the realization of the founders’ dream to preserve and restore native forest land on the bay, with access for students, families, hikers, and people of all abilities. Their vision includes learning opportunities for students from surrounding K-12 schools and the community college, student day campers from the neighboring area, and hosting a best-practices forest living laboratory. Their wish is to introduce the community to the area’s flora and fauna and its rich history, including the Yaqo’n people, the glory days of Yaquina City, and its West Yaquina suburb beckoning across Yaquina Bay.

The injustices didn’t stop there. During the allotment period beginning in 1887, what remained of the reservation was chopped up into 80-acre parcels, with 41,000 acres “given” to the remaining native people but held in federal trust. What remained - 179,000 acres - was then opened up to further encroachment by white settlers. When native people were suddenly told they needed to start paying property taxes 25 years into the allotment period, many more lost their lands to foreclosure, and those lands were snapped up by white settlers.

White settlements continued to expand and flourish on what was once land set aside by the federal government for the first peoples to live on forever. By 1900, only 500 of the 2,700 original Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians remained. By one account, perhaps 19 of those people were Yaqo’n. Today, one family remains who are known to trace their ancestry to the Yaqo'n people.

By the 1950’s, only 15% of the 41,000 acres were held by native families. Still held in federal trust, these lands were turned into fee-simple title and sold off to whomever could buy them. In a further insult, the tribe was terminated, meaning they now had no tribal rights to their land, their traditional fishing/hunting grounds, or their homes. Their sovereign rights were erased, and elders were exited from the Siletz community by white settlers, their land and homes absconded.

allotments and termination

Colonel T. Egenton Hoggnext steps

Moving forward, a broad Forest Master Plan includes goals and objectives for restoration and education to guide further development of Yakona. Two Douglas fir plantations remain to be thinned and interplanted with native trees and shrubs. Abatement of invasive blackberry in the former clear cut will continue until the young native trees gain enough size to out-compete invasive plants and shade the areas of concern. Abatement of English ivy, holly and Scotch broom will be ongoing. Development plans include constructing Yakona Learning Center, a plant nursery, and several pit toilets. A barrier-free trail suitable for strollers and wheelchairs is on the horizon. A cadre of docents continues to grow, providing much needed support in habitat management, educational programming, and access. An endowment will provide for staff and operational needs, and a conservation easement will protect Yakona in perpetuity.

legacy through partnership

Partnerships with Lincoln County School District and Oregon Coast Community College will leverage Yakona’s living laboratory and enable educational access that inspires future generations. Deep conversations with the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians have identified opportunities for youth and families to access traditional ecological knowledge and practices. Collaboration with Oregon Coast Council for the Arts, Sikta Center for Arts & Ecology, the Newport Symphony Orchestra and the Ollala Center ensure a well-rounded and accessible nature experience for all.

Yakona Nature Preserve & Learning Center allows visitors to interact with and learn about the natural world and our connection to it. Engaging children, parents, and students with the history and ecology of the land results in increased awareness and appreciation of the relationship between the health of natural habitats and the vitality of our communities. This unique peninsula, forever protected from development and rich in cultural and natural history, is a treasure for future generations of both humans and wildlife.

The success of Yakona Nature Preserve & Learning Center depends upon a steady flow of programmatic funding to support partnerships with local schools, the community college, and nonprofit collaborators. Yakona seeks partnerships to establish diversified funding streams, which include Lincoln County, the Newport community, foundations, corporations, and private donors. Perhaps you share this vision, and will join us.

The legacy of Yakona Nature Preserve & Learning Center belongs to a community – a community of people, local governments, and educational institutions. Secured for all time, this preserve will enrich the lives of countless generations and ensure that habitat for wildlife endures.

Chemawa School in Salem, OregonMap courtesy of www.neahkahnievisions.smugmug.comreferences

Castle, Darlene; Edelman, Brenda; Hughes, Meg; Hughes, Riley; Thompson, Paul (1994). Yaquina Bay: 1778-1978. Lincoln County Historical Society, Newport, OR.

Courtney, E. Wayne (1989). The Indians of the Yaquina Bay. Sanderling Press, Corvallis, OR.

Daniel, William (1999). After Lewis and Clark: Jurisdictional Issues. From American Indian Civics in Today’s Classroom. Humboldt State University, Arcata CA.

Lincoln County Historical Society (1980). Lincoln County Lore. Lincoln County Historical Society, Newport, OR.

Palmer, Lloyd M. (1982). Steam towards the Sunset: The Railroads of Lincoln County. Lincoln County Historical Society, Newport, OR.

Rutkow, Eric (2012). American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation. Scribner, New York, NY.

Tanner, William (1999). From the Indian Reorganization Act to Termination, 1930’s-1950’s. From American Indian Civics in Today’s Classroom. Humboldt State University, Arcata CA.

Wilkinson, Charles (2010). The People Are Dancing Again: The History of the Siletz Tribe of Oregon. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

Wilson, James (1999). The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York NY.

Wyatt, Steve (1999). The Bayfront Book. Lincoln County Historical Society, Newport, OR.