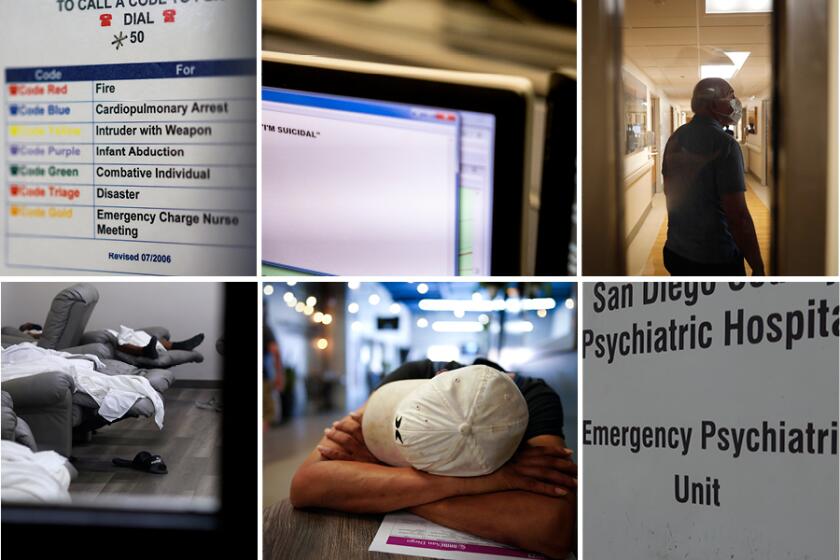

For three days last year, reporters followed patients, police, clinicians, dispatchers and those struggling for help to create a minute-by-minute account of an overwhelmed system

San Diego County has a mental health crisis.

It’s on the streets and in jails, in classrooms and suburban homes.

The problem isn’t new, but only in the past few years has it burst into the public consciousness in a way that’s forced elected leaders to pledge more and more time and money toward a fix.

Yet, by any metric, the situation is worsening.

Over the last three decades, the rate at which adults were placed on 72-hour mental health holds has almost doubled. For kids, the number has increased nearly tenfold.

Mental health calls for service to law enforcement have spiked by more than 120 percent since 2009, creating backlogs at all levels.

During a three-day period last year, from April 25-27, people sometimes stayed in crisis stabilization centers beyond a 24-hour limit set by the state because there were no hospital beds available.

The same went for emergency rooms. At one point, there were more than 40 psychiatric patients waiting in ERs for a mental health facility to take them. Rady Children’s Hospital always had at least 10 kids in a similar situation.

Read the full three-day narrative:

Things were hardly better in hospitals. During the three-day period, there were 742 psychiatric beds available in the county, and during that time many facilities reported few, if any, empty spaces.

And an empty bed wasn’t always an available bed. More than a quarter of the 60 spaces at the county’s psychiatric hospital stayed open during this period because the facility lacked enough employees to take more people, especially as some patients needed one-on-one attention every hour of the day, officials said.

Yet the region has no comprehensive real-time system for tracking when behavioral health beds are available, making it nearly impossible to know when the county teeters at capacity.

Some patients ready to leave the hospital may not be able to live on their own, but residential care facilities that provide meals and dispense medication have been disappearing. Over the past decade, the county has effectively lost 68 places that had supplied more than 500 beds, state data show.

That sometimes leaves people stranded. About half the beds at the county hospital, as well as Scripps Mercy in Hillcrest, were occupied by people ready but unable to leave because there was nowhere for them to go for further treatment.

At the end of last April, one person in Sharp Mesa Vista had been there 242 days. Scripps had a patient for 530 days. Another patient at the Psychiatric Hospital of San Diego County hit 711 days.

Those who do get out sometimes enter a seemingly endless cycle of confrontations with law enforcement. There are clinicians who help officers field some of the tens of thousands of mental health calls that come in each year, but they’re often not available and the county doesn’t track how often those psychiatric teams can’t respond.

Unsurprisingly, the largest provider of mental health care in the county isn’t a hospital system or a nonprofit or a crisis center. It’s jails.

More than a third of people jailed last April were on psychotropic medication for a mental health disorder.

But what all this looks like on an individual level — between the people struggling every day to give and get help — is often hidden, which is why The San Diego Union-Tribune spent nearly two years working to pull back the curtain.

In the first part of a three-day narrative, a woman hearing voices tells her family she’s in danger. Then she grabs two knives.

In the second part of a three-day narrative, a mother with schizophrenia heads to court. Will a judge agree she’s getting better?

In the third part of a three-day narrative, an officer at a car crash reaches for his radio to call for help. He doesn’t get to it in time.

In this Union-Tribune special report, take a deeper look at key parts of the system and the history that brought us here

They’re 911 dispatchers, doctors and judges, and they have witnessed firsthand the decline of the region’s collective mental health.

A recent survey of 1,600 San Diego County behavioral health workers revealed something stunning: 44 percent may soon seek a different job.

‘I had a very personal reason for wanting to undertake a project that would expose the frailties of San Diego County’s behavioral health system’

The Aug. 2 virtual forum tackled questions about the roots of the crisis and what the community can do to support young people.

The 72 Hours team

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.