“I’m going to get you, Mommy!”

My 3-year-old son and I are playing a hybrid game of hide-and-seek and peek-a-boo, and he’s just chased me into the bedroom. We both jump on the bed and roll around giggling when he grabs a chunk of my long hair in his little fist, pulls it and laughs at me.

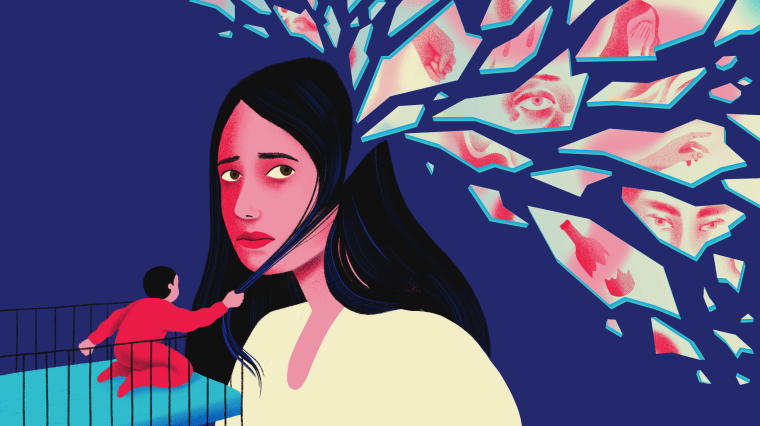

Part of healing from trauma and preventing it from becoming intergenerational relies on addressing it, being honest about it and dealing with it in a healthy way.

Within seconds, I am under the covers, cowering. Tears are streaming down my face, and I have no idea why. I just know I am hiding from my own child.

My son has no idea what’s going on, either. He thinks I’m still playing, so he jumps on top of me.

“You found Mama!” I gasp between sobs, trying to hide that I’m crying. I crawl out of the comforter, feel my way to the floor and take a deep breath. “Hey, buddy? Mama’s gotta use the bathroom for a minute. I’ll be right back.” And I slink off like a dog that’s been hit.

Splashing cold water on my face, I’m transported back in time to a bathroom in a building at the northern edge of Manhattan, New York. The sink is massive, and I want to crawl right in and slide down the drain. I’m in my early 20s, hiding from a boyfriend who has just slapped me twice across the face.

But then suddenly I’m back home, 38, in the East Village where I live with my husband, our son and our two rescue pit bulls — where I am safe and won’t be slapped or berated or sexually assaulted. Yet I no longer feel safe. I am split wide open.

My son is knocking on the door, calling out, “Mama, mama, mama.” I open the door and do the only thing I can: I gather him into my arms and tell him I love him.

It happens again the following week, when my son reaches for the spoon in my mouth and yanks it out. Once again, the tears won’t stop. But this time, I run into the bedroom and get my husband. I tell him I’m experiencing a traumatic reaction, and he needs to take over. Because I’m realizing that’s what these are: instances of post-traumatic stress disorder triggered by the absolute love of my life, my son.

When these episodes started happening, I thought I was alone — and a terrible mother — but it turns out many moms struggle with trauma triggers from their children’s behavior. Part of healing from trauma and preventing it from becoming intergenerational relies on addressing it, being honest about it and dealing with it in a healthy way, especially when it comes from unexpected places and people who have no idea the distress they’re causing.

“It’s not that I don’t want him to see me cry,” I told my therapist after my son threw a book at my face in a typical toddler move and I broke down for the third time. “Human emotions are normal and nothing to hide. But my reactions are so extreme. I don’t want to traumatize him, either.”

Modeling healthy emotional behaviors for my son is one of the most important things I can do as a mother — and with the onset of these PTSD episodes, I worried that I was failing him. It’s one thing to tell a toddler you disapprove of their actions; it’s another thing to curl up crying on the floor and be unable to stop.

With trauma, our bodies get stuck. They have good intentions — they want to protect us in the best way they know how. Unfortunately, this becomes a problem when you start to interpret nonthreatening things as threatening.

“Everything that happens to us emotionally or psychologically happens to our bodies as well. It's all connected,” Dr. James S. Gordon, founder of the Center for Mind-Body Medicine, told MindyBodyGreen. "If you look at people who go into a fight, flight or freeze response, just look at the way they hold their bodies—they're tense, they're tight, their whole body is set up to protect them from a predator."

Over the course of my mental health journey, I’ve learned that I tend to freeze — and the triggers causing this response can be surprising. Case in point: my toddler pulling my hair. Annoying? Yes. But threatening? No.

While we don’t have a choice over what triggers us, we do have a choice over how we deal with our triggers, even if it’s incredibly difficult. Melissa Kester, a marriage and family therapist who is also an abuse survivor, understands the challenge.

“When my toddler hit me for the first time, he innocently became my abuser, and I once again felt those mixed feelings of rage and terror,” she recalled. “Holding these experiences in ... and staying a compassionate, centered parent was the hardest thing I did.” Sometimes we need to accept that we can’t do it: “Make space to grieve and be at peace [knowing] that we are not perfect and no one can ever be.”

Indeed, when I’m spiraling, I’m not necessarily taking stock of the situation from the logical part of my brain. I’m all animal, a deer in the headlights. So what can parents do if they find themselves being triggered by their children’s behavior?

“Your self-care as a parent is just as important as the care for your child,” Kester emphasized. “Increase activities that build awareness and space, like a meditation practice and yoga. Nurturing positive resources like our friendships, exercise, creativity, nature, religion … are all important in this journey.”

A mother I recently spoke to with a trauma history that includes surviving a school shooting agreed that “finding ways to get some time to myself” helps her cope with her 2-year-old’s moods: “Part of it is recognizing what has caused the trigger, understanding that I'm not in danger.” She also recommended listening to music, getting outside for a walk or going to the park as a family to ease the tension.

It’s also important to respect your young child’s own experience. Toddlers are constantly testing their boundaries — it’s what they’re supposed to do at this stage in their development. When my son expresses that he does not want to be hugged, we listen to him. We hope that by respecting his boundaries, he’ll feel safer and more autonomous — and more inclined to respect others as well.

Beyond each individual relationship, society as a whole needs to be more aware that typical toddler acting-out can provoke difficult emotions in parents.

Also key is telling him, in age-appropriate ways, when he has crossed our own boundaries. Another mother I know realized that when her son hit her in the face with his Hulk doll, she “needed to work harder to instill in my child that we must apologize when we physically hurt someone and see to them to make sure they are OK; to teach him empathy.” Now that he’s 12, she said, “I feel he has a very good grasp of it.”

Beyond each individual relationship, society as a whole needs to be more aware that typical toddler acting-out can provoke difficult emotions in parents. Allison Landa, a writer from Berkeley, California, thinks the issue of children triggering their parents’ traumas is not addressed enough.

“I definitely think parents — not just moms — avoid talking about this topic,” she said. “It ain't easy. It ain't fun. It ain't pretty, and we like things that are all those things. That said, just because this is not a shiny, happy experience, it should not be avoided.”