The Pandemic of Adverse Childhood Experiences: Courts and the Health of Idaho Citizens

By Hon. Bryan K. Murray

While the world has been preoccupied with a pandemic known as COVID-19, a long-existing health crisis continues unabated causing far more long-lasting harm to society. As a member of Idaho’s bench for the past 27 years, one of my priorities has been addressing juvenile justice issues. This experience has revealed a pressing health problem known as ACEs, or Adverse Childhood Experiences.

The symptoms of this health crisis fill the Idaho Court system. What are some of the symptoms? Divorces, domestic violence, substance abuse, addictions, DUIs, mental illness, child abuse, neglect, and many more chronic problems are symptoms filling the court system. Many of the people seeking justice in Idaho courts have histories of trauma and abuse. This health crisis fills our courts, jails, and prisons.

With the outbreak of the COVID-19, the world health organizations mobilized a swift health care response. People can debate how swift the world responded to COVID-19, but what is clear is that it was not the years of delay experienced in gaining a limited response to ACEs. We now know a great deal about the health harm and society costs of childhood trauma, but there is little outcry to improve the way society prevents or responds to ACEs.

Why Should Courts Care About ACEs and What Are They?

Apart from human misery, why should we care about ACEs? The cost to taxpayers is a good reason. ACEs were named and numbered by an insurance company asking, “Why are some people so costly to insure?” The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and household challenges and later-life health and well-being.

The original ACE Study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997 with two waves of data collection. Over 17,000 Health Maintenance Organization members from Southern California receiving physical exams completed confidential surveys regarding their childhood experiences and current health status and behaviors. [i]

The original ACE study focused on 10 childhood experiences that were predictive of bad outcomes in adulthood. Through my experience, I have learned that the bad outcomes do not wait for adulthood to be seen. In children, trauma can look like ADHD, Bipolar Disorder, Conduct Disorder or “Pissed-off kid disorder.” As children go through life experiencing multiple ACEs, the chance for healthy brain development is lost and delayed.

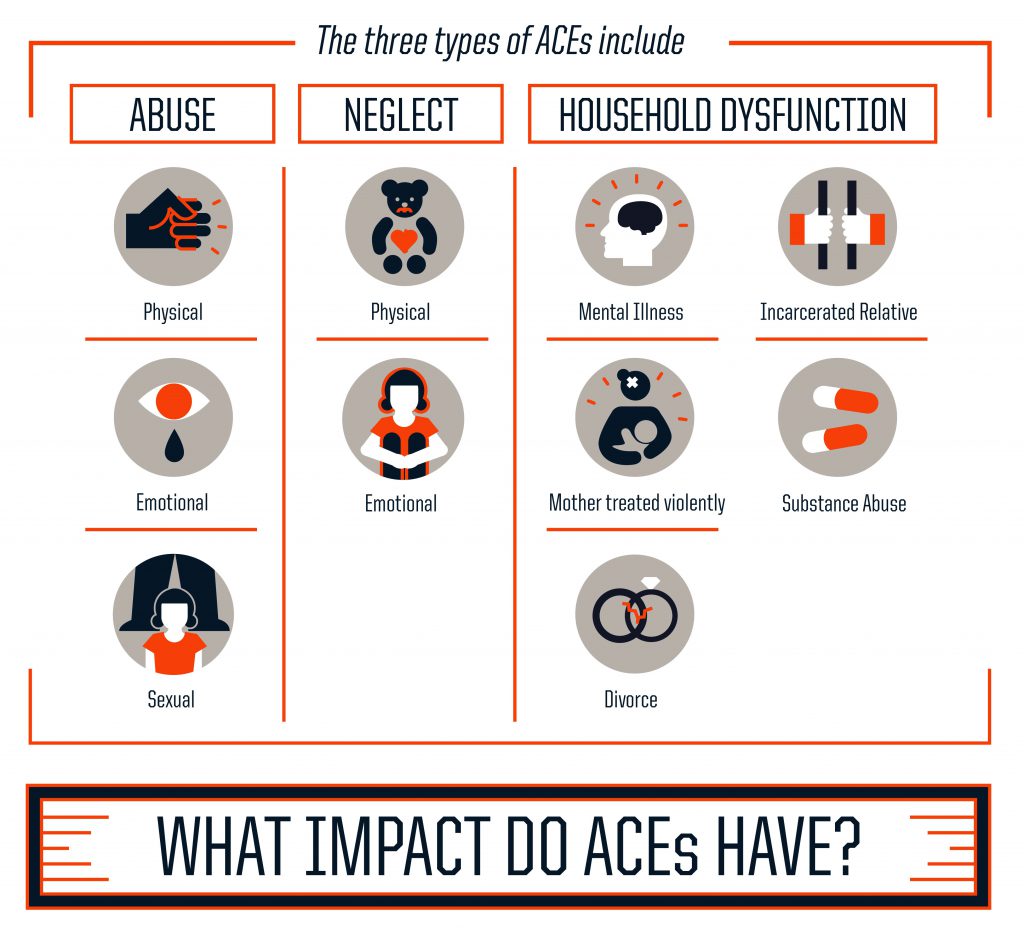

What Are the ACEs?

The 10 ACEs used as a common measurement are divided into three life areas: Abuse, Household Challenges, and Neglect. A child who accumulates more than one ACE is more likely to have adverse life outcomes in adulthood. All ACE questions refer to the respondent’s first 18 years of life. The 10 ACEs are:

Abuse

- Emotional abuse: A parent, stepparent, or adult living in your home swore at you, insulted you, put you down, or acted in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt.

- Physical abuse: A parent, stepparent, or adult living in your home pushed, grabbed, slapped, threw something at you, or hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured.

- Sexual abuse: An adult, relative, family friend, or stranger who was at least 5 years older than you ever touched or fondled your body in a sexual way, made you touch his/her body in a sexual way, attempted to have any type of sexual intercourse with you.

Household Challenges

- Mother treated violently: Your mother or stepmother was pushed, grabbed, slapped, had something thrown at her, kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, hit with something hard, repeatedly hit for over at least a few minutes, or ever threatened or hurt by a knife or gun by your father (or stepfather) or mother’s boyfriend.

- Substance abuse in the household: A household member was a problem drinker or alcoholic or a household member used street drugs.

- Mental illness in the household: A household member was depressed or mentally ill or a household member attempted suicide.

- Parental separation or divorce: Your parents were ever separated or divorced.

- Incarcerated household member: A household member went to jail or prison.

Neglect

- Emotional neglect: No one in your family helped you feel important, special, or loved. No one in your family looked out for each other and felt close to each other, and your family was not a source of strength and support.

- Physical neglect: There was no one to take care of you, protect you, and take you to the doctor if you needed it, you didn’t have enough to eat, your parents were too drunk or too high to take care of you, and you had to wear dirty clothes.[ii]

There are many other types of childhood adversity, but these 10 have been proven to be consistently predictive of trauma in numerous studies around the world, confirming the original ACE study. It should be remembered that experiencing childhood trauma can be predictive, but it is not determinative. Individuals can overcome the trauma through having or developing resiliency.

Can We Predict ACEs?

My juvenile detention center has a clinician who, in cooperation with Idaho State University, has been collecting ACE data on Idaho juveniles in detention. In the general population of Idaho teens, 45.8% have no ACEs. For the kids being booked into detention only 7.8% have no ACEs. In the reverse, in detention, 63.2% of juveniles have three or more ACEs. In the general population the percentage is 15.4%. Girls’ coming to detention have less serious crimes, but a much higher ACE count. Girls average 5.19 where the boys average 2.88 per child.[iii]

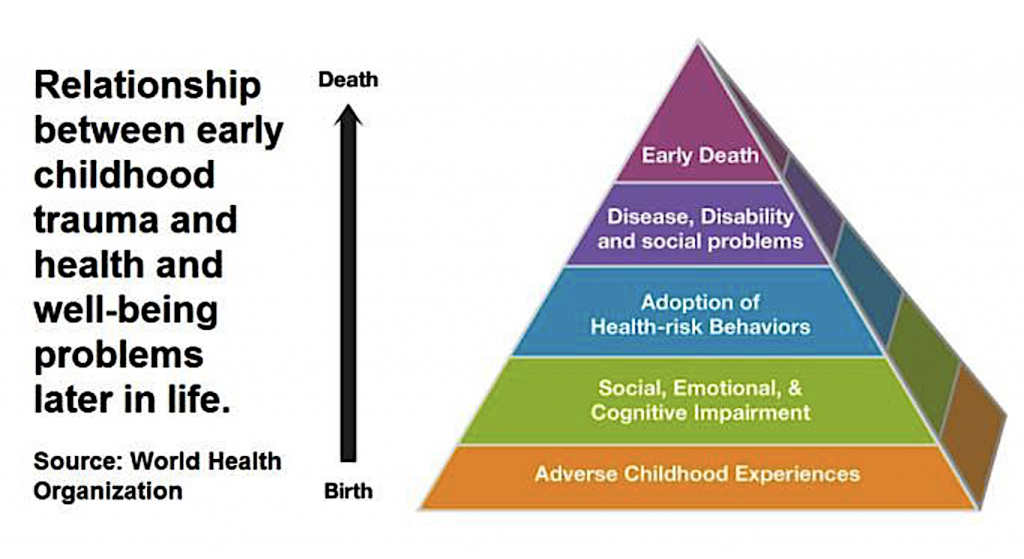

These adverse childhood experiences cause children to be more prone to aggression, delinquency, further victimization, educational failure, and involvement in juvenile justice. “The accumulating evidence for the negative impact of ACEs on health outcomes in adulthood mean that they are now considered a public health concern.” “Common behaviors of people having 3 or more ACEs include: Lack of physical activity, smoking, Alcoholism, drug use, and missed work. Physical and mental health predictable issues include severe obesity, diabetes, depression, suicide attempts, STDs, heart disease, cancer, stroke, COPD and broken bones.”[iv]

“People with six or more ACEs died nearly 20 years earlier on average than those without ACEs.”[v] Substance abuse only offers a seemingly attractive escape from past trauma without a promise of healing. J. K. Rowling, in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire observed, “Numbing the pain for a while will only make it worse when you finally feel it.”[vi] In sum, children with ACEs are likely to engage in some activity to numb the trauma that they have long suffered creating significant personal and societal burdens that cannot be ignored any longer.

Trauma Informed Courts Can Assist in the Impacts on the System and the Individual

Justice Bevan in a 2019 Idaho Supreme Court decision, State v. Eldon Gale Samuel III, 452 P.3d 768 (2019), carefully outlined the ACEs experienced by the 16-year-old defendant before he killed his father and brother. ACEs do not justify harm to others, but they do help understand cause and effect. Trauma is not an excuse, but it does explain why hurt people hurt people. Please read how Samuel was born in California and ended up in an Idaho jail and how many ACEs that he accumulated between birth and jail.

Idaho courts have become an emergency room for the treatment of trauma. Trauma makes the mind and physical body sick and the courts are on the front line of dealing with this sickness in society. Idaho judges are being trained in trauma and how to create trauma-informed court rooms.

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges defines trauma-informed courts as a public health approach, whereby there is a communal understanding of the long term impact of trauma on child and adult development, including involvement in the judicial system.[vii] The system needs more, including trauma-informed lawyers and staff. We need to be able to ask why people are making the mistakes and if the answer is trauma, have trauma-informed treatment available.

Many Idaho judges lead problem-solving court teams that focus on health issues caused by trauma. These include substance abuse, thinking errors, criminal behaviors, mental health, domestic violence, child protection, and educational failure. These courts attempt to treat the whole person and all of their needs from employment to housing and span the gap between health care and justice.

The most challenging of participants are those who have multiple co-occurring problems caused by a full list of ACEs. Without problem solving courts, many of the participants would be filling Idaho jail and prison beds. Some progress is being made in responding to untreated childhood trauma, but courts, state agencies, and private providers are spending much of their resources in serving this population without coordinated prevention efforts.

We Can Prevent, Identify and Treat ACEs

The time has come when we need to prevent ACEs, and when they do occur, provide effective treatment and response. The Harvard Center on the Developing Child provides great research and guidance not only on how to respond to the needs of this population, but also on supporting collaboration across policy and service sectors to identify vulnerable children and families that require preventive assistance.[viii]

The Idaho Supreme Court Child Protection Committee, Department of Health and Welfare, and the Department of Juvenile Corrections have been working with the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform at Georgetown University on a Cross-over youth project. A crossover youth is defined as “Any youth who has experienced maltreatment and engaged in delinquency (regardless of whether he or she has come to the attention of the child welfare and/or delinquency systems).[ix] In cooperation, a practice has been developed to identify these youth and to have a joint response to their needs, including their parents and school district that are a critical part of any plan for their success.

Opportunity for Improvement

The passage of additional child protection legislation, The Family First Prevention Services Act, or Family First at the end of 2018, provides Idaho with an opportunity to improve how we prevent child abuse. Before this act, states have received little federal support to do prevention work. Agencies have been paid only for services provided to kids in foster care. Under Family First, prevention services will be available for mental health, substance abuse, and in-home parent skill-based programs for children or youth who are candidates for foster care, pregnant or parenting youth in foster care, and the parents or kin caregivers of those children.[x] We cannot let this opportunity pass on improving how Idaho prevents or responds to children who have experienced ACEs. We cannot turn our backs and say: “It is a problem for Health and Welfare.” Health and Welfare is our state child protection agency, but our communities must become the Idaho Child Protection System.

We cannot continue to allow up to 20% of our population to suffer misery in life and struggle with health and being unproductive because of trauma experienced in their childhood. The problem has been identified. Our communities can work on preventing and then providing effective treatment for what we cannot prevent.

Giving our children a great childhood will create the way for them to be healthy productive adults.[xi]

Hon. Bryan K. Murray has been a Bannock County Magistrate Judge since 1993. Judge Murray works in the areas of child protection, juvenile justice, and civil mental commitments. he is also the Chair of the Idaho Supreme Court Child Protection Committee.

[i] https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html

[ii] Too many sources to list but I encourage you to do an internet search on ACEs.

[iii] Lynch, S.M. & Weber, S. (February 4, 2020) District VI 2016-2018 Detained Youth & ACES: Preliminary Findings 2020. Idaho State University

[iv] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6366931/

[v] Am J Prev Med. 2009 Nov;37(5):389-96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19840693 Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality.

[vi] Rowling, J.K., Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire (695).

[vii] See Trauma-Informed Courts and the Role of the Judge, https://www.ncjfcj.org/child-welfare-and-juvenile-law/trauma-informed-courts/

[viii] https://developingchild.harvard.edu/

[ix]https://www.google.com/search?q=georgetown+university+crossover+youth+practice+model&sourceid=ie7&rls=com.microsoft:en-US:IE-SearchBox&ie=&oe=#spf=1585862871768

[x] Public Law (P.L.) 115-123, file:///F:/CHILD%20PROTECTION/Family%20First/Title%20IV-E%20Prevention%20Program%20_%20Children’s%20Bureau%20_%20ACF.html

[xi] A resource on ACEs with connections to past and ongoing research and application can be found at: https://acestoohigh.com/aces-101/

Official Government Website

Official Government Website