By The Herald Editorial Board

It’s been nearly a full year without Friday night lights, the squeak of shoes on basketball courts or the ping of ball against bat at Snohomish County schools, as athletic calendars were shut down along with school buildings during the coronavirus pandemic.

That silence could end soon throughout the county, following an announced — and admittedly jumbled — schedule for Wesco schools last week, with practices for the “fall” sports of football, cross country, girls swimming and diving, boys tennis and girls soccer to begin Feb. 22, with competition perhaps starting as early as March 1.

But as high school sports happily return, more than 30 schools in Washington state — and at least one in Snohomish County — may be asked to leave behind one traditional aspect of prep athletics: high school mascots, images and logos that reference Native Americans, their culture, dress and customs.

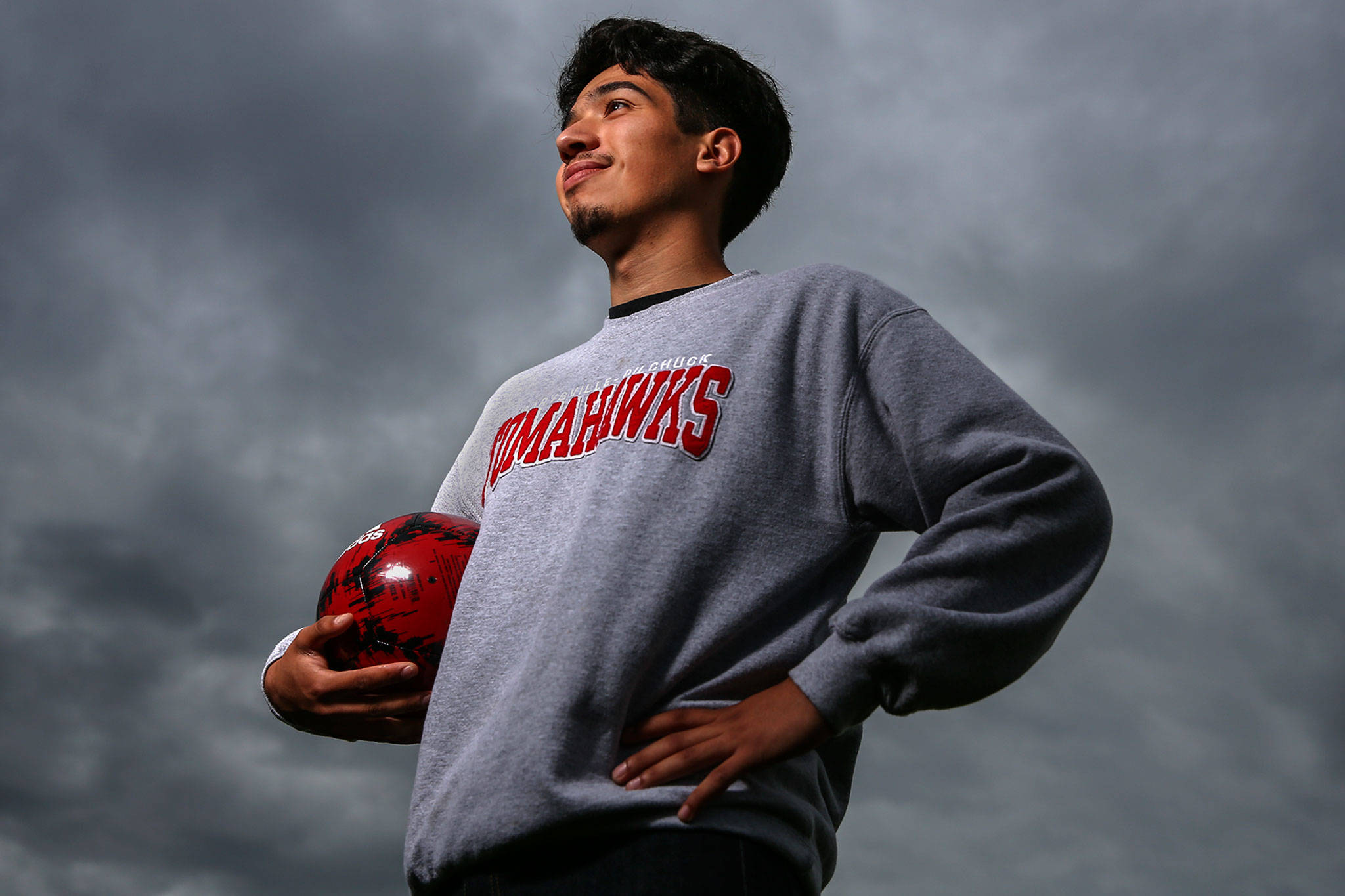

House Bill 1356 would prohibit public schools from using Native American names, symbols or images as school mascots, logos and team names, phasing out their use after Jan. 1, 2022. At least two Snohomish County schools would potentially have to make a change: Marysville Pilchuck High School’s Tomahawks and Mariner High School’s Marauders.

The bill’s main sponsor is Rep. Debra Lekanoff, D-Bow, who has been joined by co-sponsors, including Reps. John Lovick, D-Mill Creek; April Berg, D-Everett; and Lauren Davis, D-Lynnwood. Lekanoff, who is the House’s only current Native American lawmaker, is an Alaskan Native of Tlingit and Aleut heritage.

The bill’s intention, Lekanoff said, during a house Education Committee hearing last week, is to reclaim the regalia and other cultural items important to Native heritage that have been appropriated as mascots and team names.

“The regalia that Native Americans wear … is a generational, cultural teaching that runs through our bloodlines. Our regalia is the very essence of who we are,” she said. “Using them in mockery, this is not a way in which we believe we are being honored.”

The state Board of Education has previously attempted to work with individual school districts to advocate for change. The board in 1993 asked districts to review names, mascots and logos for derogatory depictions; then more specifically in 2012, asked districts to discontinue their use.

Scattered efforts throughout the state have not pushed schools to make a change.

The discussion seems especially appropriate now, as professional sports teams appear to have sensed a shift of opinion among the general public and their own fans that the era has passed for such imagery and depictions. The Washington Football Team of the National Football League last season left behind its Redskins moniker and logos, and was recently joined by Major League Baseball’s Cleveland Indians, who announced it will also change its name and logo, a move that followed an earlier decision to end use of the cartoonish and patently offensive Chief Wahoo mascot and logo.

Some fans and schools have defended the use of Native American images for team names and logos, insisting the practice is meant to honor Indian heritage and recognize ties to local tribes, even pointing to Native Americans who support — or at least do not loudly object — to the imagery.

True enough; there are school districts with significant populations of tribal students and athletes and that are within or near the boundaries of Native American tribal lands that have used the names for decades, including the Marysville Pilchuck Tomahawks. An important exception in Lekanoff’s legislation would allow schools to retain names and mascots if the tribal authority has been consulted and approves of their continued use. But that consent — specifically requested and fully discussed within communities — should be a requirement.

The use of such imagery is particularly important because we addressing names and depictions that students and young athletes wear, not only on the fields and courts, but in classrooms and in public. We tell our students that the uniforms, sweatshirts and letter jackets they wear are a statement of pride for their schools and their own achievements.

But the feeling can be one of conflict for Native American youths, said a Nisqually tribal member, testifying last week.

Chaynannah Squally, a young Nisqually leader and keeper of the tribe’s Lushootseed language, expressed her concern for how Native children and youths see themselves reflected in the depictions.

“We are not your costumes, nor are we your mascots,” she said. “We are not your warrior or your medicine man.”

Squally’s comments are backed by a 2005 resolution by the American Psychological Association that recommended the immediate retirement of American Indian mascots, citing research that showed “a negative effect on not only American Indian students but all students,” undermining educational experiences and creating a hostile learning environment.

“When our youth witness our culture used by non-natives as mockery, portraying us as aggressive, mean killing machines it is a proven fact that these messages lower self-esteem and raise negative self-image for many Native children, often expressed in the harshest ways possible by suicide, suicide attempts and other self-hating actions,” Squally said.

Students, parents and alumni take great pride in their school’s athletic teams, and they should. The games our student athletes play provide color and excitement, encourage healthy activity, build community cohesion and celebrate the achievements of students.

We need to keep in mind that when seated in the stands and bleachers, we’re rooting for the students, not the mascot.

Correction: An earlier version of this editorial misidentified the high school that calls its athletic teams Marauders. While some uses of the name Marauders have referenced Native Americans, Mariner High School’s mascot is a killer whale.

Media Player Error

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.