Surprising Benefits for Those Who Had Tough Childhoods

No one covets a stressful childhood. But the later-life benefits of growing up in a tumultuous home are beginning to come to light, upending conventional wisdom in the process.

By Megan Hustad published March 7, 2017 - last reviewed on August 4, 2022

Sarah* grew up as an only child in a middle-class Los Angeles home that wasn't nearly as sunny as it appeared from the outside. On the rare evenings when her father was home for dinner, she wished he had stayed at the office. She was used to the tension her mother alone brought to the dinner table. But having two problem drinkers to contend with was more than a 10-year-old could handle. An evening might proceed smoothly—or someone might have a bottle broken on his head.

Her childhood left an indelible impression on Sarah, who is now in her late fifties, a happily married grandmother of three as well as a published author and writing teacher. She recalls growing up "in constant emotional danger. There was never a time when I felt comfortable, when I could relax." She remembers thinking everything was her fault and says she still tends to apologize too much today. The smallest affectionate gesture can send her back to her youth, feeling trapped, anxious, and desperate for escape. "I feel sorry for my husband," she admits. "He'll take my hand while we wait at an intersection, and my gut instinct is to yank it away and start running."

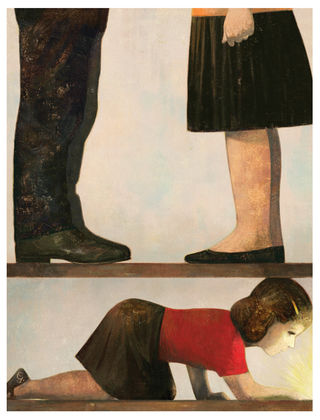

But Sarah also credits her upbringing for giving her the observational skills of a master spy. She can sense when people are hiding something from her, and her reading of the power dynamics in any room comes as if by instinct. "I can see how people stand in relation to each other in an instant," she says. "I can see where fear is coming from, where openness is coming from." The skills needed to navigate her turbulent childhood appear to serve her well as an adult.

What possible benefit is there in a tumultuous childhood? It is not an easy question to ask, particularly as each stressful upbringing is stressful in its own way. Some involve grinding poverty and some, overt abuse, while others are built on constant destabilizing neglect, or "undercare." These varied experiences are now the basis of cross-disciplinary research indicating that stories like Sarah's are not just the result of make-lemonade-out-of-lemons pluck. Early lives shape the very hardware of our brains, leaving some people impaired in certain respects, but others measurably stronger. As it happens, some of the adaptations taken on by children in stressful environments can come in handy later on.

Few who suffered deeply during childhood would wish the same experience on their own children. But as one self-identified survivor of a painful childhood concludes, "I'd be lying if I didn't acknowledge that misery benefited me in some ways."

A New Perspective

The downsides of a rough upbringing are well-documented. The standard model holds that early suffering leads to further setbacks as an adult because those who emerge from a punishing childhood are so damaged by those years that they may never live up to their full potential. They may be more prone to depression and score lower on tests of intelligence and memory. They also appear to be at greater risk for a range of physical ailments, from chronic back pain to heart disease.

Adults who experienced significant childhood stress can display a hostile attribution bias, meaning they perceive threats in situations that others properly view as neutral. Such a cognitive glitch can hamper the ability to form the kind of alliances that professional and social success most depends on. "It is essentially a biological phenomenon," or a dysregulated fight-or-flight response, says Daniel Keating, of the University of Michigan. "It means that the system designed to regulate your stress response is either undershooting the mark or overshooting it." Overshooting leaves you "reacting to things that are not significant threats in the world, but are either imagined threats or neutral things that you interpret as threats." It also makes you slower to return to your baseline. The effect can produce kids more likely to act rashly, even when unprovoked, who turn into sullen, withdrawn adolescents and, perhaps ultimately, adults who fly off the handle without warning.

But a nagging sense that the conventional wisdom painted an overly hopeless picture prompted Willem Frankenhuis and Carolina de Weerth, of Radboud University in the Netherlands, to publish a well-cited review suggesting that the script could be flipped, or at least amended. Recent studies had shown that individuals who'd had chaotic childhoods exhibited an enhanced ability to detect and monitor threats and to recall negative events. Was it possible that, under the right conditions, kids from stressed environments would perform better than expected at efficient information gathering, assessing people's reputations, and other reasoning abilities?

"Most of the research on young people from adverse environments focuses on what they're bad at," says JeanMarie Bianchi, of Wilson College. "Our goal has been to uncover the psychological strengths of this population, because we know very little about what they're good at."

Researchers who have pursued this work, like Vladas Griskevicius, now at the University of Minnesota Carlson School of Management, see the core question as a natural outgrowth of life history theory, which proposes that people structure their lives depending on their childhood environment. Broadly speaking, those who grow up in safe, predictable environments with adequate material resources tend to employ "slow" strategies—they study hard, delay gratification, put off marriage and reproduction, and generally follow the advice given to most middle- to upper-middle-class kids on how to stay on that course. Those who experience considerable upheaval early in life tend to employ "fast" strategies—for example, having sex earlier or becoming parents at a younger age. The fast strategist's "reward horizon" is shorter, and their future less assured; they will take a smaller immediate reward instead of a larger payoff later.

But instead of thinking in terms of whether a slow or fast life strategy is "good" or "bad," couldn't one think in terms of what was appropriately adaptive in each environment? A child growing up in a stable, loving home who is presented with a candy bar and told that if she waits a half hour, she can have two, would be wise to wait. But if her home is chaotic and her caregivers deliver only sporadically on their promises, it would be quite reasonable to take the candy bar while the getting is good. Grabbing what you can when it's in front of you in this context is not "impulsive" or "shortsighted," as those behaviors are typically—and disparagingly—labeled. It's strategic.

To assert that the latter behavior is adaptive is one thing; to say that a harsh or unpredictable childhood environment could yield objective future benefits is another.

The Upside of Unpredictability

To pursue the question of potential upsides of chaotic childhoods, Griskevicius and a team led by Chiraag Mittal focused on two elements of executive function: inhibitory control, or inhibition; and task switching, the ability to disengage from one task and pick up another. They hypothesized that people who grew up amid unpredictability would fare worse on measures of inhibition but better at task shifting, especially in situations that evoked elements of their childhood.

They primed half of their subjects to think about instability by having them read an article titled "Tough Times Ahead: The New Economics of the 21st Century"; the other half read a text about a person looking for lost keys. In computer-based challenges routinely used to measure inhibition, people who grew up in unpredictable environments showed no significant difference from their peers under the control condition of having read the article about the keys. Primed with the article about economic uncertainty, however, they performed significantly worse.

The results were different when it came to task shifting: In the control condition, the two groups performed similarly. But in the uncertainty condition, those who experienced unpredictability in childhood outperformed their privileged peers—they were faster in shifting focus without a loss of accuracy.

Developmental psychologist Bruce Ellis of the University of Utah describes this trait as the ability to "unstick yourself," a type of cognitive flexibility that correlates positively with traits such as creativity. It may be that individuals raised in stressful environments have a greater willingness to leave something undone—a lack of perfectionism that helps them do what's necessary without dwelling on what could have been—compared with those raised in homes with the luxury of routinely expecting perfection.

"We are not in any way suggesting or implying that stressful childhoods are positive or good for people," Mittal and Griskevicius have insisted. Still, a closer look at the potential strengths of every individual, no matter his or her background, could help overturn stereotypes, both in the culture at large and in the minds of those who have grown up in uncertain environments that tend to foster self-doubt.

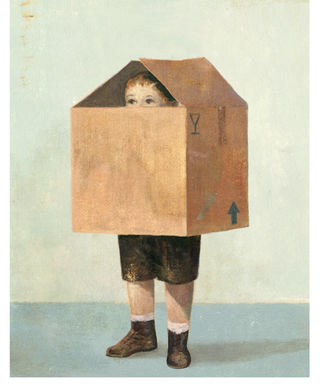

Kids who grow up feeling that nothing is under their control may turn into adults who don't particularly value feeling in control, but that could be an asset for those making their way in a treacherous economy. Consider Steve*, a New York-based software developer whose most vivid childhood memories of Christmas involve hiding under the couch in the basement to avoid getting caught in his parents' verbal crossfire. "They spent so much time fighting with each other that they did not have much energy left over to tend to us," he says. Steve recalls wanting to help around the house, but never being told what to do or, when he completed chores, whether he had done an adequate job. Around age 10, he started cutting his arm with a razor blade, hoping to get attention—to no avail.

"Even during the good times there was a sense that you were on borrowed time and disaster was just around the corner," he says. "And it always was."

As an adult, though, Steve has proven to be highly flexible, with a willingness to take significant risks with little hesitation. He is sure that his upbringing has helped him through rough career patches. When facing big questions—where to work or how much to invest in a relationship—he has a high tolerance for ambiguity, for living in that in-between stage in which one does not know whether success or crushing failure awaits.

Evidence of other possible cognitive advantages is gradually emerging. Chiraag Mittal, now at Texas A&M, is looking into the effects of childhood environment on memory. His early findings indicate that people who grow up in unpredictable environments are better at what's known as working memory updating; they have the ability to forget information that is no longer relevant and to attend quickly to newer data that is.

Bianchi believes that growing up with stress may promote certain forms of associative learning—the ability to recognize that multiple elements of one's environment are connected in some way or that certain behaviors will be rewarded or punished in a given scenario. Growing up in an environment that's constantly in flux, she says, may make people "more aware of and responsive to changes in the environment." In the lab this means subjects may be quicker to perceive that they have been given wrong instructions to a computer game—and to change their behavior accordingly. "This would have profound implications," Bianchi says. It means that people who are used to being able to rely on rules and to trust instructions—such as those who grow up in more stable environments—may stick with the rules even in the face of negative results. Meanwhile, those from stressful backgrounds may be quicker to explore other possibilities and stumble upon novel solutions.

Sorting It Out

Stress is not one-dimensional, and while socioeconomic background is a factor in examining its effects, it is far from the only one. Clear childhood stressors such as divorce; domestic violence; physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; and the mental illness, alcoholism, or drug abuse of a household member are not limited to any one demographic. Growing up in poverty but with a stable family life poses different challenges than, say, being raised with the trappings of privilege but knowing that an otherwise indifferent parent's affection is contingent on how well you perform. Several cultural critics, surveying the state of the millennial generation, suggest that those within it who had upbringings high in parental praise but lacking in competition have too little experience with loss and may now lack confidence, resilience, and decisiveness.

The amount of stress one experiences in childhood also appears to be a factor in predicting future cognitive benefits. A pair of longitudinal studies by Mark Seery, of the University at Buffalo, found that people who reported experiencing moderate stress throughout their lives tended to score higher on measures of resilience (and were less likely to have chronic back pain) than those who reported either little stress or extreme stress.

The re-evaluation of stressed childhoods is part of a larger reconsideration of the mental and physical impact of stress. Of particular interest is the effect of norepinephrine, a chemical messenger that's triggered to help us pay attention when we notice something new, unexpected, or frightening. In moderate doses, it can be a "sort of wonder drug to the brain," says clinical psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist Ian Robertson, the author of The Stress Test. Norepinephrine helps the brain make new connections, with positive effects for both learning and memory. There is also something of a reinforcing loop between norepinephrine and IQ; the higher your IQ, the more norepinephrine is released when you're faced with a challenging problem.

This hormonal effect may help explain why those raised in tumult could be better and faster at assessing threats—for example, reading emotions or intent in other people's faces. There may a tipping point, however. Too much stress, Robertson says, can lead to excess norepinephrine production and an ensuing, cell-damaging flood of cortisol, which in excess can lead to vascular difficulties in midlife and is associated with early mortality.

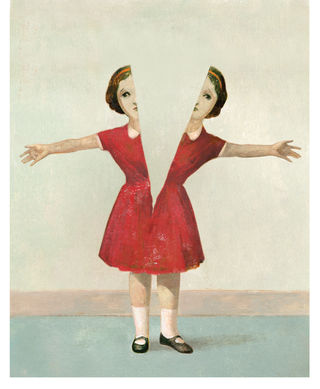

"The effects of stressors depend on many factors," says Frankenhuis, now codirector of the Research Network on Adaptations to Childhood Stress at the University of Utah. Innate biological differences in temperament, driven by a combination of inherited genes, can promote profoundly different responses to similar upbringings and lead to starkly different adult outcomes even for individuals within the same family. Positive aspects of an otherwise highly stressful childhood can also blunt the effect, such as optimal nutrition or supportive extended family members. And the varied types of stress in tumultuous households—for example, acts of commission vs. those of omission—can affect children in different ways, Frankenhuis maintains. A slap in the face is not the same as a failure to console a crying child, though both have consequences.

Someone like Sarah, who grew up in a home inundated with persistent emotional stress and tension—conditions that emotional intelligence and acuity could potentially mitigate—may emerge with stronger, or different, cognitive benefits than someone raised in an environment where "blunt force" stressors like physical abuse could not be prepared for or dodged in any way.

Crafting Happier Endings

Left alone with an abusive, paranoid schizophrenic mother for much of her childhood, Lillian*, 85, admits to being generally suspicious of people's intentions. But she is also extraordinarily willing and able to shift directions—her CV includes stints as an actress, portrait painter, theater professor, college dean, community organizer, and entrepreneur. Her husbands' careers required several moves, including an extended stay in Japan, forcing Lillian to routinely adjust her own professional goals. "I had no difficulty doing this," she says. "I counted on the permanence of nothing in my life except my ability to meet the challenge of change."

Greater knowledge of the cognitive adaptations that stressed kids like Lillian tend to make could lead to curricula and school environments more geared toward their strengths and attentional styles. Today, Ellis says, most interventions for kids identified by teachers or social workers as high-risk take their metaphorical inspiration from cats' claws—kids "come into school like a cat with its claws extended." And all efforts to help them are variations on "trying to get the cat to retract its claws—to be more trusting, to be more comfortable in school, to be more connected to the teacher." In other words, they are pushed to act more like kids from low-stress, low-risk environments. But reprogramming people is hard, he says, and educators could find it easier to work with children's adaptations rather than fighting them.

Tumultuous childhoods, as novelists and therapists have long known, can make for more complex and compelling characters. "People who haven't suffered are as interesting as shrubbery," says therapist Ian Morgan Cron. "With happy people," he half-jokes, "you think, Oh man, I can't get any purchase in this conversation with this person, because there are no cracks."

But Cron has seen in his practice how growing up in a culture steeped in negative assumptions about one's intelligence, temperament, and mental state can lead an individual to play out self-fulfilling prophecies: I'll never recover from what I went through. I didn't have the foundation you need to get the most out of life. Skeptical of their own prospects, such people might shy away from opportunities or get lost in the pain and bitterness of their experiences.

While a fuller understanding of the effects of chaotic beginnings gain societal traction, individuals who can learn to grapple with the stress of their past and overcome bleak views of their future can generate new hope. "We are the stories that we tell about ourselves," Cron says. "At group retreats, I ask people to turn to the person on their right and say, 'Would you please just tell your life story in five minutes, in which you appear as the victim?' When that's done, I say, 'Now turn to that same person and tell the same story from the perspective of you as the hero.' And they say, 'What? Is that allowed?' Well, sure.

"You have agency in this matter, even without revising history. It happened. We're not going to deny the facts," he says. "But the way we interpret history is up for grabs, and it can have a tremendous amount of healing power."

People who have already embraced every aspect of their past don't need convincing. "I'm not a denier, but rather a realist," says Lillian, who recently self-published her first novel. "I've learned to creatively change what can be changed and to live with what can't be altered. And I always turn to the fact that I'm still here and actively in the mix. I strongly believe that we all have so much more within us than we allow to develop. The possibilities are endless—not threatening."

*Names have been changed.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.

Facebook image: All kind of people/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: davide bonaldo/Shutterstock