Indian River Lagoon Gains Widespread Attention for Algal Blooms, Fish Kills, and Manatee Deaths

Though less than four feet deep and rarely wider than four miles, the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) plays a tremendous role in east Florida’s environmental health and tourist economy. The lagoon’s regional significance raises the stakes surrounding major environmental crises in recent years. Fish die-offs, polluted water, dying seagrass, harmful algal blooms, and increasing manatee deaths directly impact the 6 counties and 38 cities that border the IRL, as well as the 1.6 million area residents.

In 2015, The IRL Council convened with the goal to protect and restore the lagoon through the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Estuary Program. Supported by research from organizations like Florida Atlantic University’s (FAU) Indian River Lagoon Observatory, the IRL Council is dedicated to protecting the lagoon through collaborative monitoring efforts. The IRL Council recently became a SECOORA member to further share their monitoring data and make the data more widely accessible.

Florida Atlantic University Leads the Way With Water Monitoring Sensors

Dr. Dennis Hanisak, FAU professor and Indian River Lagoon Observatory Director, explains that continual, robust water monitoring is critical to managing concerns like harmful algal blooms and coastal ocean acidification.

Dr. Hanisak stated, “Florida was engineered to drain water off land and into salt water as quickly as possible. And it’s very efficient at doing so. But the result is that all of this stuff is going into the lagoon– stormwater, pollutants, turbidity from land use, and nutrients from runoff.”

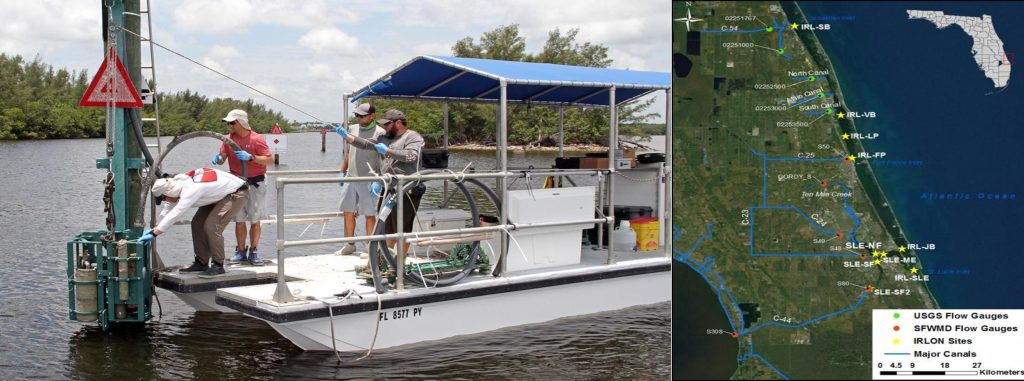

The Indian River Lagoon Observatory Network (IRLON) has established a network of sensors within the lagoon to collect a wide range of biological, chemical, and physical data parameters useful to organizations who seek to make informed decisions regarding the lagoon.

Whereas Dr. Hanisak remembers an era when collecting monthly water samples was considered robust, he now says, “We need constant monitoring to understand things like algal blooms and track the progress of our restoration efforts.”

Using systems like IRLON, allows researchers to constantly monitor and create baselines of “normal” ecological conditions. Having baseline data is needed to make comparisons of our changing, complex ecosystems to determine causes for events like the increasing manatee deaths in IRL.

Preventing Manatee Deaths Requires Focus on Both Lagoon Monitoring and Infrastructure

Since the lagoon’s massive fish kill of 2016, a recent spike in manatee deaths is the most recent biological crisis to receive media coverage in the lagoon. Florida has seen over 403 reported manatee deaths since January 2021, 304 of which occurred in Brevard County bordering IRL.

Polluted runoff into the lagoon creates a nutrient imbalance that results in harmful algal blooms, which in turn reduces oxygen and sunlight cannot penetrate into the water column. This results in seagrass die off. Manatees depend on seagrass as a primary food source for survival. The IRL lost half of its seagrass coverage in 2011, and has seen sporadic declines in recent years. The loss of food is suspected to be the cause of manatee mortality.

IRL Council Executive Director Dr. Duane De Freese notes the heightened concern around manatee deaths from starvation due to seagrass die off. The Council feels the root cause lies in the excess nutrients from wastewater and stormwater which are negatively impacting the IRL’s seagrasses and decreasing the system’s carrying capacity.

Dr. De Freese states that while “there is no shortage of need to answer the big questions we have about harmful algal blooms,” monitoring must be coupled with infrastructure changes in order to help restore the IRL.

Ongoing Lagoon Research is Critical to Florida’s Environmental Health

While there is no silver bullet to restore the lagoon and protect the economies and communities that rely on it, Dr. De Freese advocates for significant investments in technology to accelerate both monitoring and infrastructure improvements.

In the meantime, the IRL Council and FAU will continue monitoring parameters such as nutrient levels, salinity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen and work towards expanding their data collection to include CO₂ and chlorophyll.

Dr. Hanisak says, “It’s bad, but in a positive sense it’s an enormous opportunity for students coming into this now. For people interested in environmental questions, having the tools to get decent baseline data is richly rewarding.”

Related news

New High Frequency Radar at the Dry Tortugas National Park Improves Ocean Surface Current Measurements Across the Straits of Florida

A new CODAR Low-Power SeaSonde HFR has been deployed by the University of South Florida at Fort Jefferson on Garden Key to measure surface currents to improve understanding and prediction of the Gulf of Mexico Loop Current.

President Biden Proposes Significant Budget Cuts to IOOS for 2025

President Biden’s recent 2025 budget proposal slashed the funding allocated for the Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS) by 76%, which would effectively shut down coastal and ocean observing efforts.

Webinar: NOAA Resources to Help Coastal Communities Understand Flood Risk

Join us Wednesday, March 27th at 12 PM Eastern Time for SECOORA's Coastal Observing in Your Community Webinar Series to hear from Doug Marcy with the NOAA Office for Coastal Management.