You can’t effectively study the Great Lakes by simply looking at them from above the water. All the action lies beneath the surface. That’s why the UWM School of Freshwater Sciences has used a research vessel on Lake Michigan for more than 50 years.

Called the Neeskay, the vessel is an Army T-boat built in 1953 that was bought and converted to accommodate research in 1970 by the school’s predecessor, the Center for Great Lakes Studies.

The Neeskay is the only research vessel that sails year-round on the Great Lakes, logging more winter cruise time than even the vessel operated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. So, what is the job of a research vessel and how does it benefit science?

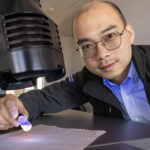

We spoke with the Neeskay’s new interim captain – Max Morgan, who is also a graduate of the School of Freshwater Sciences, and Professor Harvey Bootsma, a veteran researcher who relies on the boat for access to the depths. Morgan and Bootsma dive into their jobs by answering some questions here. To hear the entire podcast, go to WUWM.com or get Curious Campus on your favorite podcast app.

Max, you came to UWM to get your master’s degree in freshwater sciences after you had worked as a crew member on the EPA’s research vessel, the Lake Guardian. Tell us about that.

Morgan: I was the head marine technician on the Lake Guardian. So I was in charge of all the scientific equipment and all the data that we collected on that equipment. I had to organize all the scientists’ projects because there were always a bunch of different parties doing research on the ship.

There’s a difference between operating the ship and doing science on the ship. As captain of the Neeskay, I have knowledge of both, which is useful to help the scientists obtain the best results, whether that’s from equipment or the maneuvering of the ship.

What does it mean to have access to a vessel specifically outfitted for research?

Bootsma: One of the things that attracted me to UWM was the fact that there was a research vessel that we could use on Lake Michigan – and also the fact that the research vessel was right next to our laboratories on the Milwaukee harbor. I’ve worked in other places around the Great Lakes, but nowhere have I been in a laboratory where it’s been so easy to move from the lake to the lab. So it’s really an incredible tool.

Give us a description of a research project that couldn’t be done without the help of this vessel.

Morgan: Recently we’ve been putting buoys in the lake for the summer season. We have a few buoys in the Great Lakes Observing System – the GLOS network – that we service. One brand-new one is off of Racine, and we have one in out from Atwater Beach. And we have another one up in Green Bay. These give real-time weather data, lake conditions – like wave height and water temperatures at various depths in the water column. And you can text each buoy on your phone to obtain data. It will text you back!

I’m 6 foot 4 and the buoy is taller than me and quite heavy. The one we put out in Racine was in 135 feet of water, and that requires a lot of planning because, in addition to the buoys themselves, we also have to attach two concrete anchors to it – or sometimes we use railroad wheels which are about 500 pounds each. And then we have hundreds of feet of chain that goes up to the buoy. The Coast Guard has to know each location, so you have to be fairly precise with where you put it.

Bootsma: A lot of our research looks at how an invasive species, quagga mussels, have changed the way Lake Michigan works. And initially, over 15 years ago, we started doing that in the near-shore zone, where most of these mussels were.

But then they expanded and now they cover virtually the entire bottom of the lake. In the near-shore zone, we can work with smaller boats. But that’s not possible when you get into deeper water.

So, with support from the National Science Foundation, we’ve been looking more closely at the deep-water communities of these invasive mussels to understand how their altering both the structure and the function of the lake. That requires a larger vessel to get out in the open waters and get equipment on that vessel down to the bottom of the lake to see what’s going on.

The mussels are really efficient filter feeders. They are able to eat a lot of the plankton in the lake, which is why Lake Michigan is so clear. But that also means that there’s not as much food at the base of the food web. So it’s not as good a place for fish to live now as it was 30 to 40 years ago.

Fundraising is underway for a replacement of the Neeskay, which has already been named the Maggi Sue. Talk a bit about where we stand in that effort, and then where we’re going.

Morgan: This new vessel has been the talk of the town lately. We have about $13 million raised out of the $20 million that we need. Some of that goes into building the ship and some of that also goes into the first few years of operating the ship.

Most research vessels on the Great Lakes have been old, refitted work boats or fishing boats. This would be the opportunity for us to build a research vessel from the keel up.

The Neeskay can only travel at around 10 mph, so it’s not very fast. This new vessel will be much faster, and we’ll also have something called “dynamic positioning.” That’s where I can put in coordinates and we can hold the boat in that exact position without dropping the anchor – even with high winds and strong currents. That is key for launching scientific equipment, because most of the time, you have to be very still and be right over a certain point.

And we’ll have a much larger range. Many times, you do have to do projects overnight because some creatures only come out at night. So this would give us an opportunity and really expand the things that we can study.

Bootsma: There will be a few big advantages. One is just having a larger vessel. The Neeskay has been great, but Lake Michigan is more like an ocean than a lake and it gets rough out of there and, even in a ship as big as the Neeskay, you’re limited in the conditions in which you can go out on the lake.

Also, we use the vessel a lot for education for our students here at the school, both the undergraduate and the graduate programs, and you can only put so many people on the Neeskay. It’s often difficult to get a whole class of people on it.

And there are new types of equipment, for example multibeam sonar, that we hope to have on the new ship.