What marine life are the ‘winners and losers’ of El Niño?

A forum at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla explores the impact of the periodic climate pattern on various species amid expectations that it will hit this year.

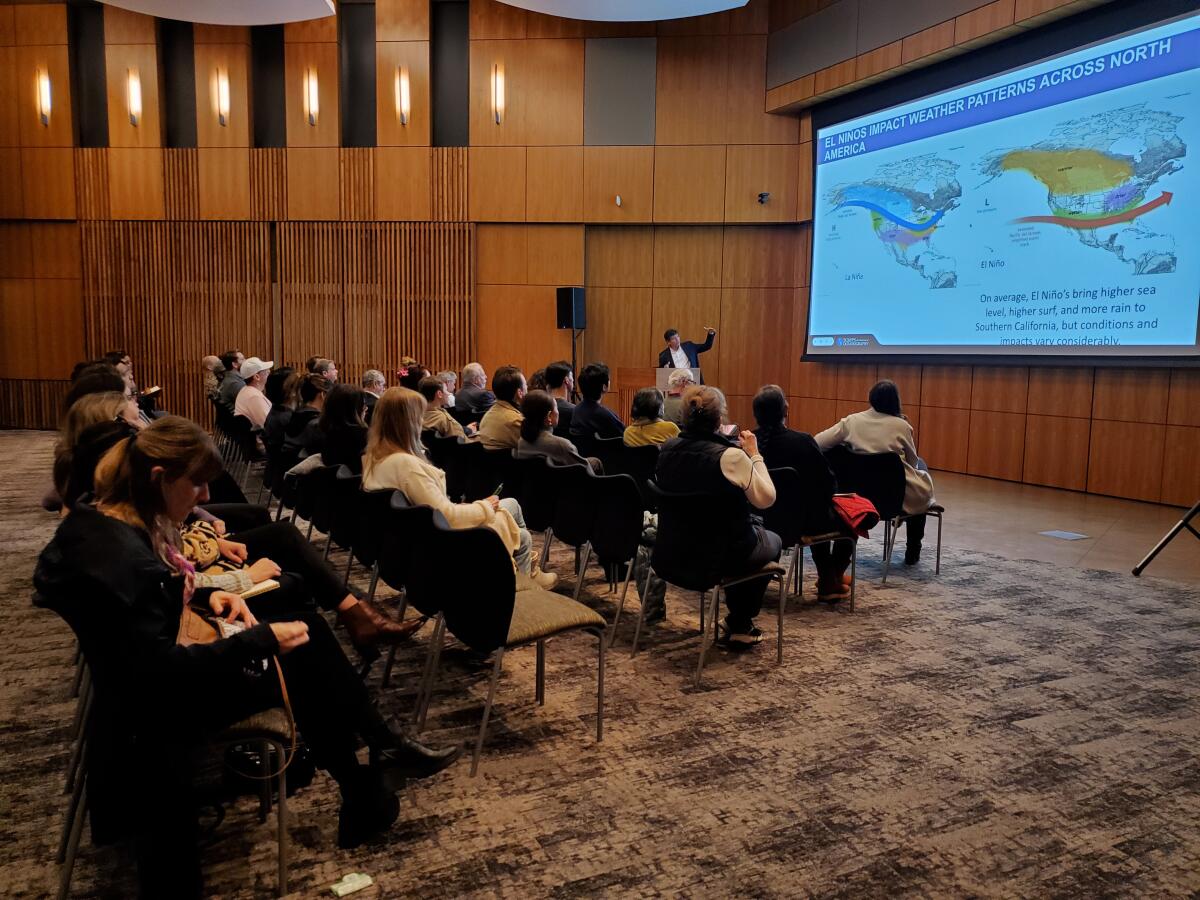

With storms fresh in people’s minds due to this week’s rains that caused flooding and massive damage in many parts of San Diego, UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla hosted a forum about El Niño storms — a phenomenon that is expected to hit California this year.

The Jan. 23 panel discussion — coincidentally held the day after a storm more powerful than expected dropped record-setting rain around the region and triggered city, county and state emergency declarations — featured four professionals in the field covering ocean observations, new methods to measure storms associated with El Niños, the relationship between El Niño and atmospheric rivers and more.

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.

El Niño is a natural climate pattern centered in the tropical Pacific Ocean in which trade winds that usually blow west along the equator, taking warm water from South America toward Asia, weaken and warm water is pushed east toward the west coast of the Americas, according to the National Ocean Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The warmer waters cause the Pacific jet stream to push farther south than normal, bringing some very wet weather to areas that don’t usually get it.

El Niños show up about every three to seven years and typically last nine to 12 months, according to Scripps Oceanography. Though they can produce storms beyond what Southern California residents are used to, they don’t just affect humans.

Under normal conditions in the Pacific, cold, nutrient-rich water rises from the ocean depths — a process called upwelling. But during El Niño, upwelling weakens or stops, and without the nutrients from the deep, there are fewer phytoplankton off the coast, according to the National Ocean Service. That affects fish that eat phytoplankton, along with everything that eats fish.

Clarissa Anderson, a biological oceanographer and executive director of the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System at Scripps Oceanography, said that “where El Niño leads to warmer temperatures, it also leads to lower nitrate [production]. The nitrate availability means the major producers in the ocean, [such as] algae and microalgae, plankton and kelp, do not have access to the kinds of nutrients they might have otherwise, which they need to grow.”

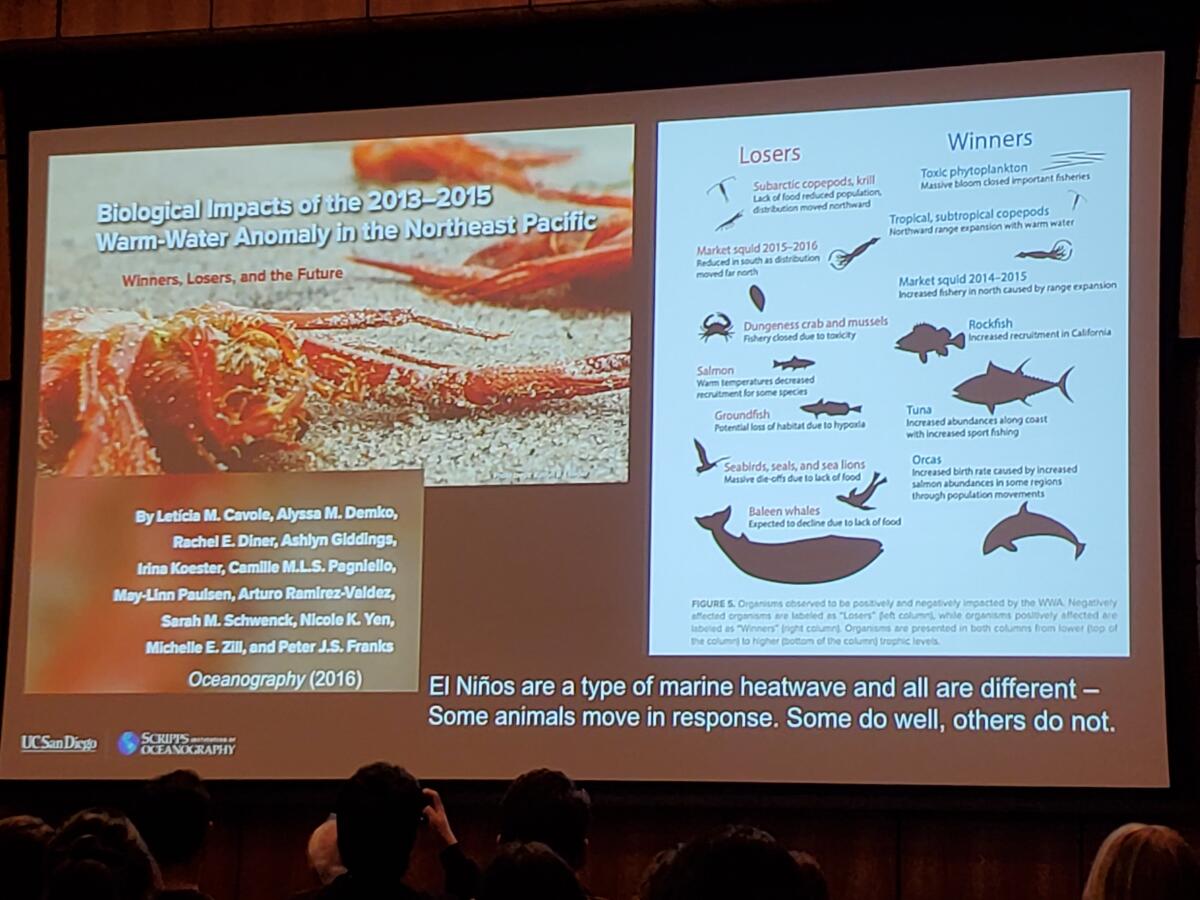

That can have a ripple effect on other organisms, she said, resulting in “winners and losers” among marine life.

“One of the animals that has a very tight correlation with El Niños is the common murre [sea bird],” she said. “It tends to feed a lot on juvenile anchovies and juvenile rockfish, and those organisms are often highly affected by that decrease in primary productivity from the low nitrate. So we see a crash in those animals often associated with El Niños.”

However, “winners” in an El Niño include toxic phytoplankton (paired with the “loser” Dungeness crab that eats them and accumulates the toxins) and tuna, which may be drawn by the warmer water to areas that normally are too cold.

In La Jolla specifically, El Niño could impact the sea lion colony at Point La Jolla. Sharon Melin, a California sea lion research leader for NOAA, said last year that sea lions during the winter “are nursing or pregnant or both. ... When an El Niño comes through … it warms everything up. So if it gets warm, that causes the prey to either move out of the area to find colder water or swim deeper in the water. If it gets too deep or too far, the sea lions can’t get to it. That can compound and ... the pregnancy is impacted. Often what we see is sea lion premature birthing or females not giving birth because they can’t maintain their pregnancies. It affects the number of pups born.”

Other local challenges come with the high surf associated with El Niños, which can create stronger waves and possibly increased coastal erosion and can damage aging infrastructure such as the seawall at the Children’s Pool.

Forecasters expect a return this year of the phenomenon that brings ‘anomalously wet conditions’ to California, including San Diego.

Anderson said she often is asked whether El Niños will lead to more harmful algae blooms like those in central California that led to the deaths of hundreds of marine mammals in 2022-23.

NOAA Fisheries reported that the Channel Islands Marine & Wildlife Institute fielded more than 1,000 reports of sick or dead marine mammals between June 8 and 14 last year that were thought to have been exposed to a toxic algae bloom. The rapid growth of the algae pseudo-nitzschia causes the production of a neurotoxin called domoic acid.

Sea lions sickened by the algae also have bitten beach-goers in Southern California recently.

“A lot of people have the expectation that not only will there be more toxic blooms but we will see more animal strandings as a result of that,” Anderson said. “Those data don’t align as well as we might like them to. In the anecdotal space there is one story, but in the statistical data space there is another story.”

Professor Bradley Moore wants to provide fishermen, governments and others a heads up when toxic algae may impact marine animals.

One of the largest “domoic acid events” of recent years predated an El Niño the following year, Anderson said.

One species whose response to El Niño is a mystery are the orcas that have been seen off Southern California recently. “It’s anybody’s guess how they will respond,” Anderson said. “They were winners [during the last El Niño]; maybe they will be again.”

Kelp is another form of marine life that is affected by the heat associated with El Niños, she said. “We have a lot of fish that thrive in these kelp forests … and [kelp] do not do well during El Niño years. ... One of the more predictable aspects of the California ecosystem is that the kelp forests respond fairly rapidly to these decreases in nitrate, and that comes in the form of biomass kelp canopy cover.”

Though kelp can respond after an El Niño year by regrowing, other stressors happening concurrently might slow that process.

“They don’t always recover,” Anderson said. “If you have an El Niño event followed by some other stressors like an urchin explosion that is taking it down, there is going to be a slower response.” ◆

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.